Why Bitcoin? How Money Works Today

Part 3: Fractional reserves, inflation, quantitative easing, and real money.

In this series on Bitcoin and money, Crypto Briefing takes a deep dive into the complexities of the modern monetary system and how Bitcoin, as the ultimate hard money, can serve as a solution to many of its problems.

In Part Three of the series we examine the forces that shape current monetary policy. The full nine-part series is available here.

So far in this series, we have examined the history of money and found that hard money has consistently returned to dominance time and time again throughout history.

Following this, we considered the differences between two of the hardest forms of money to produce; gold and Bitcoin. Bitcoin, it turns out, has a few distinct advantages over gold whilst retaining the qualities that make gold such an excellent hard money.

Today, we examine the current monetary situation around the world, which now operates under a global fiat monetary system that relies heavily on the American dollar for settlements between economies.

Fractional Reserves Undermine Money

One should not overlook the importance of fractional reserve banking and the impact this innovation had on the generation of wealth over recent centuries. This approach to generating profits on savings and loans allowed for enormous economic growth, beginning in 14th century Europe.

Fractional reserve banking as a practice is often traced back to the Renaissance era, during which such investment innovations were first made famous by the Medici family of Florentine Italy.

In essence, fractional reserve banking is the act of a bank taking a deposit from a client and thus holding a reserve of value that is tied to the value of the deposit. However, if it stopped there, it would not be “fractional” in nature.

Importantly, the bank allows the withdrawal of said funds to other clients as loans, keeping only a fraction of the original deposit in reserve. A simple example expresses the enormous monetary expansion that can take place within such a system.

Consider the following scenario:

Bob deposits $1,000 in the bank. Ten percent of the deposit must be held in reserve, according to central bank policy, so the bank allows another client, Joe, to borrow up to ninety percent of the $1,000 deposit, which Joe then uses to buy a car.

The car dealer then deposits the proceeds of $900 in the bank. Now, $1,900 magically exists from the original deposit of $1,000.

The bank then loans out ninety percent of the $900 that is now available. This pattern of depositing and lending fractions of deposits continues until eventually the $1,000 that Bob deposited has expanded the circulating amount of money to approximately $10,000.

Bob could at any point withdraw his $1,000, which probably wouldn’t be a problem since many other clients are also depositing funds from which the bank can generate loans.

What would be a problem, however, is if Bob, Joe, the car dealer and all the other depositors in this chain of fractional saving and borrowing decided to withdraw funds all at once. This would cause a “run on the banks”.

Fiat’s Fractional Reserve Issues…

This might seem merely hypothetical and unlikely to actually occur, but it happens frequently in fractional reserve banking systems around the world.

If a bank is even suspected of not holding enough funds in reserve, clients may become nervous and feel more financially secure holding cash rather than trusting that their bank is actually solvent. Bank runs have occurred from time to time in all kinds of situations, even in relatively stable economies like the United States.

Among the most well-known of these bank runs took place in 2008 during the housing meltdown, when the IndyMac bank saw depositors withdraw approximately 7.5% of the bank’s deposits after finding out the bank was not viable.

Other long-trusted banks like Washington Mutual and Wachovia failed around the same time due to massive bank runs as depositors rushed to withdraw their funds in the panic caused by the housing loan collapse.

Despite these fiascos, banks around the world continue to operate on slivers of reserves, lending out funds far beyond the actual monetary supply available to them in deposits. In America, most banks of significant size are required to hold around ten percent of deposits in reserve, like the amount used in our previous illustration.

The Federal Reserve can change this minimum to increase or decrease the money circulating in the economy.

Banks can also gain interest on reserves as an incentive to keep a healthy quantity on hand, although the exact percentage that constitutes a “healthy reserve” is highly subjective.

The European Union, for example, operating under the rules of the European Central Bank, only requires banks to hold one percent of deposits in reserve. This means 99% of deposits can be recirculated back into the economy, essentially fabricating money with extremely thin safety rails to hold things together.

The possibility of bank runs becomes significantly more likely in such scenarios. Amazingly, central banks in Canada, Sweden, and Australia have no reserve requirements whatsoever!

Quantitative Easing Undermines the Dollar

To be clear, the phenomenon of fractional reserve banking is a fundamental driver of growth in successful modern economies. In and of itself, it is not necessarily detrimental, but has been shown to be problematic when reserves are not maintained. Where it gets really problematic is when it is mixed into a potent monetary cocktail with other modern economic phenomena including quantitative easing, interest rate manipulation, and currency conflicts.

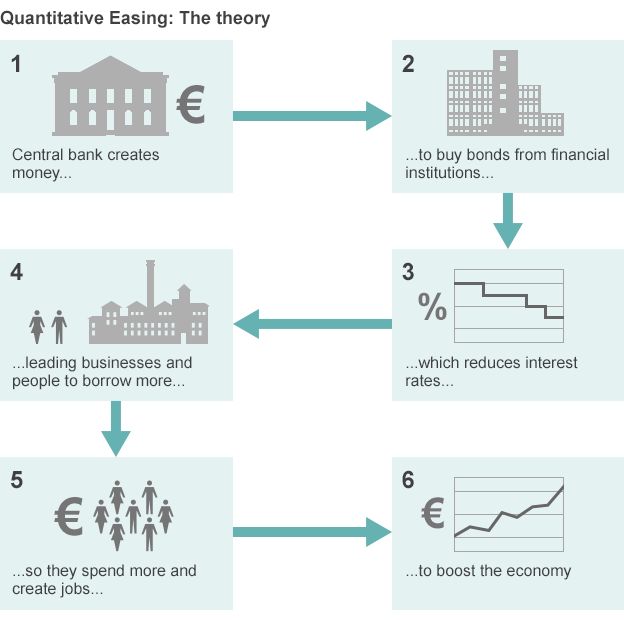

Quantitative easing, or QE, is a complex affair involving open market operations between central banks and member banks that cause monetary expansion, meaning more money moving around in the economy. The central bank buys securities from member banks, generating liquidity in the economy. It sounds complicated, but the effects of it are really quite simple.

When the Federal Reserve performs this quantitative easing, it allows banks to have a greater quantity of money than they need in their reserves. Naturally, banks would then be expected to lend out these funds for further profits.

Other elements of QE, such as the purchase of Treasurys, force interest rates downward and allow for more borrowing and spending to stimulate the economy. Ultimately, quantitative easing prints money, which has significant implications and effects on the economy as a whole.

It should be noted that the process of QE did enjoy some success in eradicating subprime mortgages and in keeping the economy afloat, at least artificially. The fact that banks did not lend out as much as expected, instead investing in stock buybacks that garnered them enormous wealth, kept perceived levels of inflation from spiraling out of control, at least in the early stages of the strategy.

As of now, bank authorities have tentatively declared an end to QE, generally considering it a moderate, or even under-appreciated success.

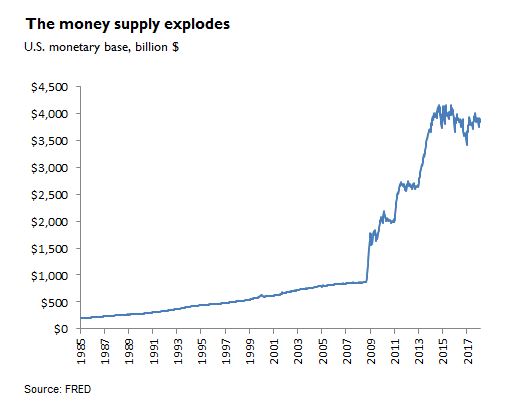

But quantitative easing appears to be irresistible to policy-makers, having been used four times since 2008. Many argue it will continue to be used ad infinitum, despite assurances to the contrary from the powers-that-be. Each time it is used, the money supply grows, and the value of each dollar diminishes relative to assets that store value.

The global value of gold and real estate has grown enormously over this past decade, at least partly, if not entirely, due to QE policies. Many consider this massive monetary supply boost to be the root cause of highly fragile asset bubbles that are destined to pop at some point.

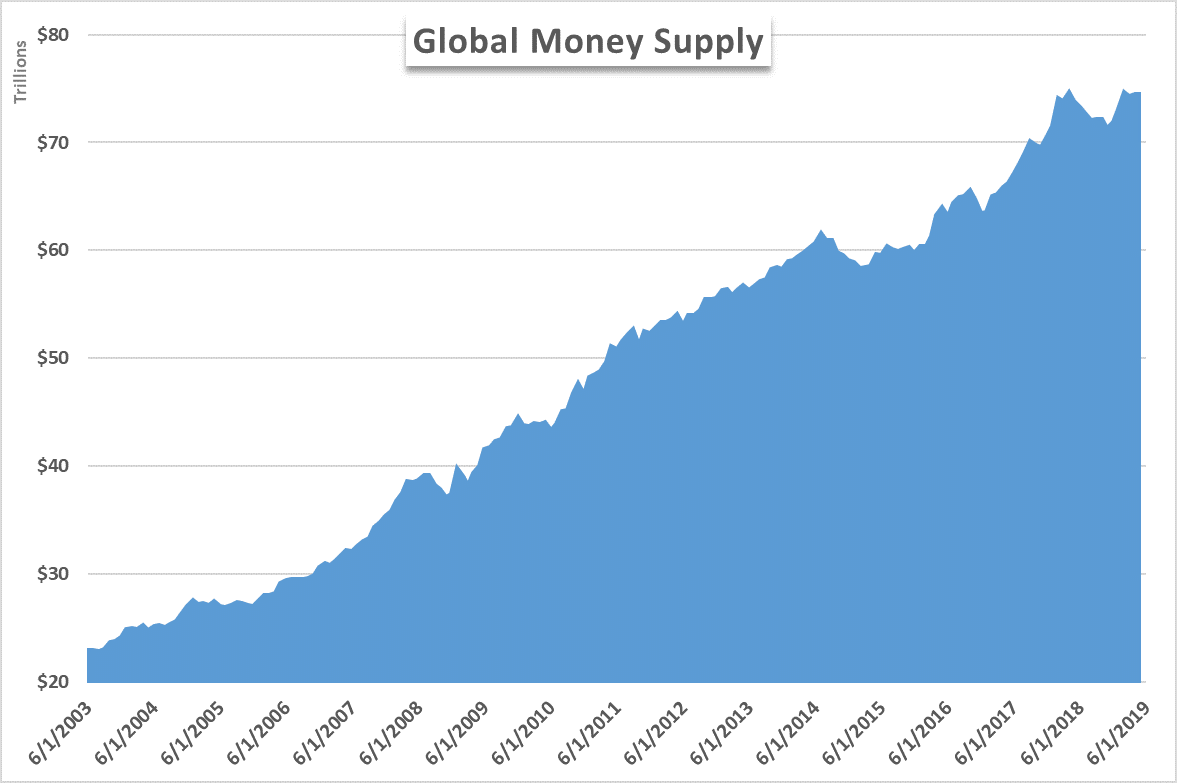

The USD money supply has grown tremendously during the past decade of repeated QE monetary practices, causing the potential for huge asset bubbles. As much of the world follows in-step with USD currency policy, the global money supply can be observed to follow an identical pattern.

It bears mentioning that Bitcoin was born at the beginning of the decade of monetary experimentation known as quantitative easing, and has seen astronomical growth in value over this period of time.

Due to the tiny volume and speculative nature of Bitcoin investment, however, this growth in Bitcoin’s market value is not necessarily evidence of causation by QE. Growth in gold and real estate prices as well as indebtedness, on the other hand, demonstrate a clear causal relationship, deeply affected by the phenomenon.

Yet, the status of Bitcoin as a store of value certainly becomes more convincing when considering the economic implications of QE strategy.

Inflation Undermines Money

The most obvious result of QE policy is the resultant inflation that occurs due to an expanding money supply. Paired with low interest rates approaching zero or even negative territory, assets have seen precipitous growth as the wealthy seek shelter for their monetary holdings in stable hosts.

Foreign real estate investment has become highly problematic in countries such as Canada and New Zealand, causing residents to struggle in their quests to find affordable housing. Instead of using homes as a place of residence, properties are bought and held as stores of value, rather than storing fiat currency that is steadily diminishing in relative value. Both countries have attempted to quell foreign interest in their housing markets with foreign buyer taxes and, in the case of New Zealand, outright bans on foreign ownership of real estate.

This problem is worsened by low interest rates that encourage higher pricing as borrowers qualify for ever-higher mortgages.

Low interest rates approaching, and at times, surpassing zero, can further compound the problem with the current trend toward cashless economies. A number of countries in the European Union, including Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden, have established federal interest rates in the negative range.

Negative Interest Rates Undermine Money

The goal of negative interest rates is to stimulate spending artificially due to the lack of legitimate demand in the economy. Rather than holding money, it is better to spend it, as borrowing is incentivized over saving.

These same countries are moving away from cash as a currency, relying instead on digital money which is on a constant path toward inflation, diminishing in buying power as it languishes in digital bank accounts. This situation is sometimes referred to as a zombie economy, where free market dynamics have faded and the economy is instead artificially propped up, with no real incentives for long-term investment.

It’s worth noting that just a few days ago, Donald Trump suggested that the US move to a negative interest rate economy.

In this sense, inflation is ultimately another form of taxation that is cleverly deceptive… in that it does not appear as such. Governments are able to spend money without needing to plead with voters to increase taxes. Rather, nations can print money as desired, reducing the power of money held in the bank accounts of unknowing citizens, all while assets and everyday living needs continuously creep upwards in cost.

It is because of the creation of easy money that this combination of inflation-inducing events is at all possible. Without easy money, zombie economies would be staved off as fractional reserves would be held in check, quantitative easing would be impossible, and inflation would be much more gradual and benevolent.

De-dollarization, Its Meaning for Bitcoin

While hard money like gold and Bitcoin exhibit free market value through the natural dynamics of supply and demand, fiat currencies only manage to maintain value via trust and ultimately, coercion.

The American dollar has succeeded as the dominant fiat currency with which the world trades due to international agreements and global dominance in military power. This role as the dominant world reserve currency is precarious, however, as economies, especially those hostile to the United States hegemony, look to alternative means for the settlement of their international transactions.

The usual approach to such a move by a hostile nation is to impose sanctions. In more severe cases, the enforcement of USD as reserve currency is carried out via outright depositions of governments, as witnessed in Libya, ongoing in Venezuela, and potentially in the early stages of taking place in Iran at the time of this writing.

The Middle Eastern nation that has a long and complicated history of conflict and American intervention stands out as a key oil supplier for China, exporting more than 20% of its crude product to the country. China, along with India, remain defiant against US-imposed sanctions, continuing to import Iranian crude oil despite the objections.

And this is just an example of where things are moving in today’s monetary environment. A growing list of nations are losing interest in accepting the settlement of international transactions in USD.

The European Union, dissatisfied with America’s unilateral withdrawal from the “Iran Nuclear Deal” or JCPOA, has gone to significant lengths to skirt around sanctions on Iranian oil by settling transactions with the country in a sort of barter-like arrangement. Russia, China, India, and Iran are leading the way in a “worldwide backlash” against the dollar, choosing other sovereign currencies and even hinting at returning to settlement in gold, instead.

This return to trusting gold and barter over fiat currencies should set off some bells for anyone who has read our previous articles in this series, where we discovered that, throughout history, economies return to hard money after experiencing failures with easy money.

Of course, the last time that nations agreed to settle international transactions in hard money, Bitcoin — the hardest money ever created that is, in many ways, superior to gold — did not exist.

In an effort to retain global currency dominance as it slowly slips away, the United States might resort to deliberately weakening their own currency against competing nations. This sort of currency manipulation is achieved via interest rate controls and money printing, using the aforementioned quantitative easing strategy.

By lowering the value of the currency, exports remain buoyant and trade surpluses can theoretically be achieved. However, this tactic often results in a “race to the bottom” as competing nations take the same approach, weakening their own currencies against each other in a downward spiral of “tit for tat”.

This approach further exacerbates the growing problems of inflation and asset bubbles that force people to turn away from trusting currencies and instead choosing to hold their wealth in stores of value that can not be controlled by central parties. Thus, the shift toward gold and eventually, Bitcoin, builds momentum.

Due to the combination of these economic forces — fractional reserve banking, quantitative easing, and currency conflict — we are witnessing the potential for a massive shift away from the easy money of fiat currency, dominated by the United States, to free market reliance on hard money, on a global scale.

In Part Four of this series, we will turn our attention to banks, and how they work – with particular attention to the extraordinary profits they command, the systematic defrauding of their customers, and the tens of billions of dollars they have paid in fines as a cost of doing their business without morality. It might get a little crypto-maximalist in places.

Earn with Nexo

Earn with Nexo