Why Bitcoin? History of Money

Part 1: What is Bitcoin and why does the world need it?

Share this article

In this series on Bitcoin and money, Crypto Briefing takes a deep dive into the complexities of the modern monetary system and how Bitcoin, as the ultimate hard money, can serve as a solution to many of its problems. We begin the series with an examination of the history of money.

Money. It makes the world go round. It has an inestimable effect on our everyday lives, yet we often take the way it works, and its history, for granted.

To gain a better understanding of money and how Bitcoin may serve society as the ultimate form of real money, let’s begin by looking at monetary systems, innovations, and the problems they faced in different places and periods in time.

Time and time again, one can observe that society gravitates back toward ‘real’ money.

Before money: the barter system

Despite its simplicity, bartering continues to hold some advantages to this day: when one barters, there is no need for money as goods or services are directly swapped. There is no need for any kind of intermediary to decide whether one should be allowed to make a trade or to determine that such a trade is fair.

One can find ancient examples of systematic bartering going as far back as the Phoenicians of 6000 BCE, who traded goods between a variety of cities across the Mediterranean Sea.

Bartering was also a common system for trading goods between the Far East, the Middle East, and Europe for many centuries, with traders exchanging spices, silks, salt, furs, perfumes and a variety of other desired goods between civilizations.

Bartering endures today and in some ways has made a bit of a comeback due to a variety of internet services that enable this form of non-monetary trade on a broader scale.

From Barter to Currency

In previous centuries, certain barter goods like weapons, furs, silks, spices, and even salt blurred the lines between bartering and money, with certain commodities eventually becoming a standard item of trade in the place of directly swapping goods or services. Some of these items became currencies, acting as a unit of value that had a standardized, agreed-upon worth.

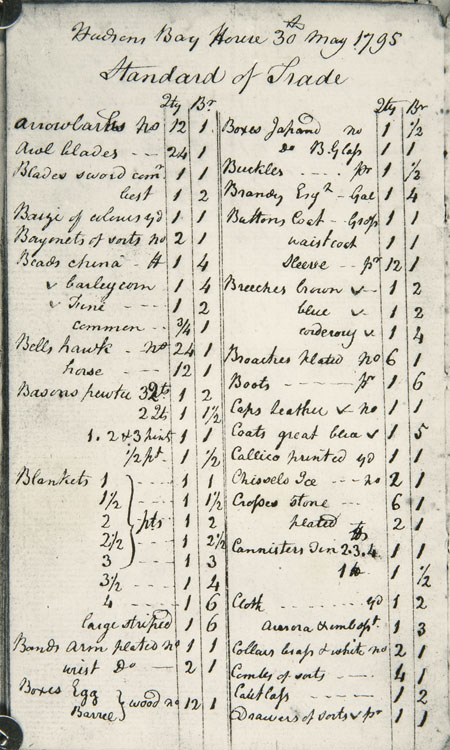

British North America serves as a fairly recent and interesting example of a transition from barter to currency economies. The “made beaver”; a single high quality beaver skin, became a standard unit of account for the trading of a variety of items during the fur trade boom of the 17th century. The made beaver acted as a currency, buying eight knives or a kettle in 1795. Ten made beaver pelts could buy a gun.

The made beaver was, in essence, a currency, but only a mediocre one. Strict standards were enforced regarding the value of a made beaver in relation to goods. It successfully acted as a medium of exchange, enabling trade, and behaved as a unit of account for determining value. It was not divisible, however, and was only somewhat fungible as long as pelts met a given standard.

Managers of fur trading companies were occasionally caught attempting to trade low quality furs in the place of the higher quality made beaver currency. Thus, it was not entirely fungible and was also nowhere near as portable or durable as metallic coins could be.

Another big problem with made beavers as currency? Beavers mostly died out in the 1800’s, leaving few of the young beavers available for trading towards other goods.

The obvious solution, at least from our perspective today, was to use coins, such as the British shilling, to make trading more efficient: as long as traders were able to come to an agreement regarding the value of the traded coins in comparison to the furs.

This move from bartering to currency has taken place time and time again throughout economic history. Yet, bartering maintains its place in society for certain situations.

What Makes Money, Money?

So what exactly makes money, money? After all, if a beaver skin could be considered a currency, isn’t it really a form of money?

Not quite. Money differs from currency in a few subtle, but important ways.

Money is a little more abstract than currency. While currency is a tool used for trade, money is something which contains intrinsic value and does not need value to be assigned to it by any authority.

More often, the expression “hard money” is used to evoke the idea of an item such as gold or silver, that holds intrinsic value because it is difficult to acquire; whereas currency is often a paper or other sort of promissory item that is used to represent value and is comparatively easy to produce.

For money to be considered real, it must meet a sort of checklist of attributes:

- Money must be a medium of exchange. In other words, it must be able to be used to trade for goods or services instead of exchanging another good or service, as in the barter system.

- Money must be a unit of account, being interchangeable with goods or services at a set price.

- Money must be portable. It has to be able to be transported from one user to another to complete a transaction.

- Money must be durable so that it can be used over a relatively long period of time without breaking down and becoming worthless.

- Money must be divisible in order to make purchases of various prices.

- Money must be fungible, meaning each unit is the same as the next. A particular dollar has the same value as another dollar.

A Store of Value

Importantly, real money is distinct from currency as it is also a store of value over a long period of time. Currency does not have intrinsic value, but is a tool that can be used to transact value. Because governments can print currencies continuously, the production of currency transfers wealth—or the actual value of real money—to the governing powers, once the currency is issued.

For the best example of real money that has persisted over the past many centuries, look to gold. Gold can not be printed, so it maintains its scarcity, unlike printed money. It endures in monetary value regardless of the value of a given currency at a given time.

While paper currencies come and go, often diminishing in value over time, gold has retained value as hard money for millennia. Unlike many currencies, gold endures; it can be melted down or converted into jewelry or electronics, but it does not corrode or break down (at least, not in human lifetimes!) and continues to exist indefinitely in various forms.

The gold that existed thousands of years ago still exists today, in some form.

Historical Attempts at Currency

We need to go back to ancient times to find our first examples of currencies created to serve economies.

Electrum is one such example—a gold and silver alloy, sometimes referred to as green gold. The naturally occurring alloy also contains traces of copper and other metals. It consists of many impurities, and varies greatly in size, quality, and density. Still, it was useful as far back as the Old Kingdom of Egypt, nearly 5,000 years ago, where it was used for exterior coatings on pyramids and obelisks, as well as for drinking vessels.

Electrum saw widespread usage as a currency during multiple centuries from the 7th century BCE to about 350 BCE. The alloy was more durable than the much softer pure gold, and refining gold to purity was much more of a challenge than it was in the following centuries, when refined gold and silver coins became the norm. The key problem with electrum was the variations in purity that made it unsuccessful in the long term as a truly fungible currency.

Over time, the amount of gold in an issued electrum coin was reduced. Because gold retains its intrinsic value, the coins would cost more than their assigned value if the proportion of gold to other metals was maintained.

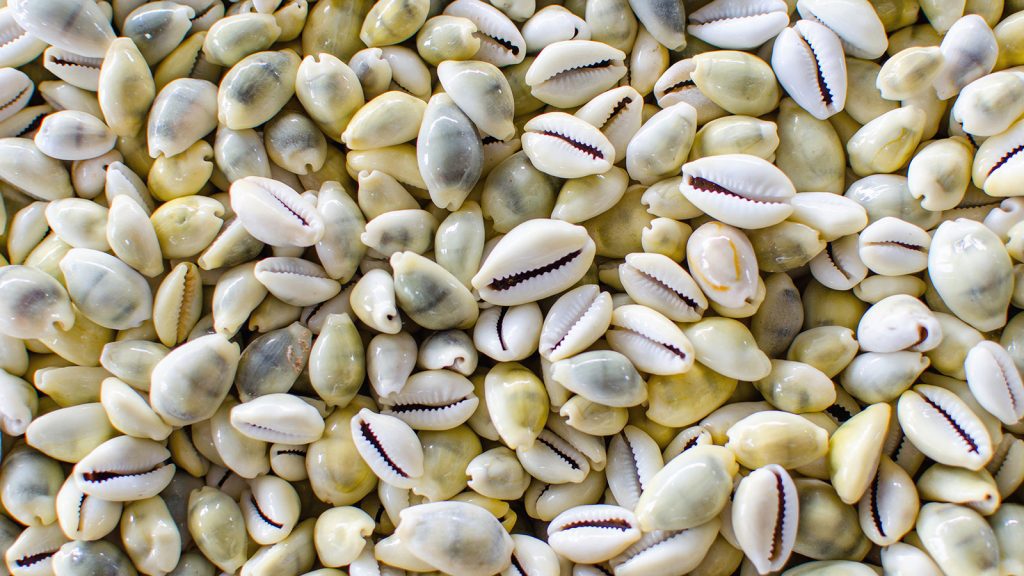

Other cultures in different time periods came up with a variety of currencies to serve their economies. The cowrie shell was traded across regions including Africa, China, and India, being useful as a currency since it was distinctly shaped, small, and light. Its fine and detailed texture made it nearly impossible to counterfeit. The shells traded for hefty sums of goods in regions that lacked natural supplies.

Chocolate, in the form of cocoa beans, was an excellent form of currency for the people of the Aztec culture over a period of a couple centuries. Like today’s paper currencies, not just anyone could produce the cocoa beans; production was controlled in order to ensure its value could be maintained. This form of money allowed for the trade of goods all over much of what is now Latin America.

Rice played the role of money in feudal 17th century Japan. One could exchange rice for goods, use it to pay taxes, and even pay workers’ wages with the grain. Being very light and easy to transport, rice enjoyed utility as a currency for many years in Japan. In fact, the shift from rice to metallic currencies was first met with considerable uneasiness and doubt.

All of these currencies operated under the basic premises of consensus and supply and demand.

In these societies, a consensus existed that agreed to assign a value to an item that might have been seen by outsiders as an irrational and worthless value. Yet, the currencies worked at some level because the society that traded them agreed to their value, and thus allowed for trade and economic interaction via the currencies.

The basic premise of the free market principle of supply and demand also held true and consistent with this system, as an over-supply of shells rendered them worth considerably less than they were in distant locales where they were difficult to attain. Still, these currencies had their limitations and could not fully replicate the characteristics of real money.

A Return to Real Money

Throughout the world’s economic history, one can observe a predictable return to real money from flawed currencies. As far back as the 7th century BCE in Greece, gold and silver staters were used for trade, and are the earliest known examples of real money.

These coins, which began as electrum, but eventually were refined and met all the characteristics of what real money should be, endured for centuries. Beginning as ingots and later being developed into coins, the stater was a trusted and stable form of money for close to 800 years.

Because of the use of gold in the coins—a hard money which maintains intrinsic value due to its scarcity —the comparable wages of people 2000 years ago in gold is nearly equivalent today:

“In the era of Emperor Augustus (27 B.C. to 14 A.D.), a Roman centurion was paid 15,000 sestertii. Given that one gold aureus equaled 1,000 sestertii and given there was eight grams of gold in an aureus, the pay comes to 38.58 ounces of gold. At current prices, this is about $54,000 per year.

…

The centurion who commanded 80 legionaries is roughly equivalent to a U.S. Army captain. The current wage for a captain is $46,000—which is fairly close. This implies that gold is a good store of value. Essentially, gold is a good inflation hedge—but our examples are over the very, very, very long term, more than 2,000 years.” (source)

Still, paper currencies offered greater convenience and ease of use, as seen in the next example from China’s long and varied history with money.

Flying Money

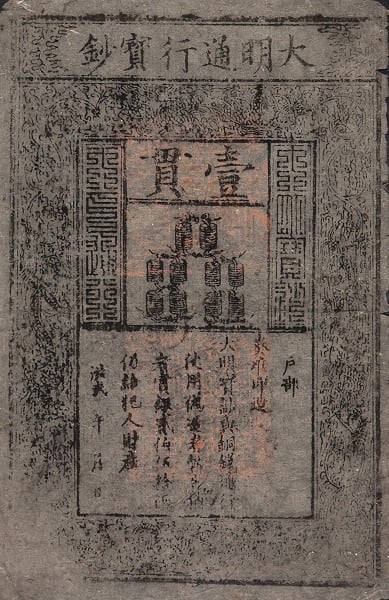

We must look to the Tang dynasty of China for the earliest example of paper currency. This currency was known as “flying money” because of its novel tendency to be blown away in the wind, unlike metal currency.

In 800 CE, the government replaced copper coins with the revolutionary paper currency. The metal currencies were in short supply and were inconvenient for long-distance trade between merchants, so the new paper currency was seen as an elegant and innovative solution. The new paper currency saved the need to ship large quantities of metal currency to far-flung merchants.

Although it wasn’t technically considered legal tender and was intended to be “cashed in” for metal currency, it was used as such by merchants because of its convenience and portability.

The first state-backed and enforced printed currency was established during the following Song Dynasty (1024 AD). Only these official banknotes, issued by the government, were permitted as currency, and were backed by the metal currency of the era.

Inflation Rears Its Ugly Head

It was during the Chin and Yuan dynasties that we see economies fall victim to the temptation of over-printing—using paper currencies that were not sufficiently backed by hard money (in these cases, copper and silver). In an attempt to maintain monetary controls, silver and gold were confiscated by the state. Eventually, however, these paper currencies collapsed due to inflation as the over-zealous printing of currency, in a futile attempt to buoy the economy, resulted in extreme inflation.

During the following Ming and Qing dynasties, a gradual return to hard money took place after failed attempts at paper currencies. The innovation of paper currency eventually spread westward to the Middle East, and then to Europe, with Sweden being the first European country to issue a paper currency in 1601.

As can be seen in the long history of money in China, economies are inevitably drawn back to metal currencies as a true hard money that can not be printed into oblivion. In societies around the world, economies eventually gravitate toward hard money due to its natural free market advantages and enduring resistance to inflation, thanks to its undefeatable scarcity.

Fiat in Modern Society

During the 20th century, much of the world’s paper currency was somewhat protected from the extremes of inflation due to the requirement that the currency be “backed” by gold or silver.

After learning the lessons of inflation with the Continental Currency of the late 1700’s, America turned to a standard that was designed to prevent such a failure. Backing each U.S. dollar with gold or silver ensured that the currency represented a genuine value. Being more rare than silver and less prone to excessive supply spikes, gold eventually took over as the standard backing for U.S. currency, with the ability to cash in dollars for the equivalent value in the rare metal.

When countries veered away from the gold standard during times of war, for example, citizens often turned to hoarding metal currencies to protect themselves as bank runs revealed an inability to access paper currency funds.

After World War II, the Bretton-Woods system established an agreement whereby currencies all over the world tied their value to the U.S. dollar, which rested on the gold standard. This meant that virtually all global currencies were linked to the value of gold, creating a global standard for money.

Of course, it’s one thing to say money is backed by gold—actually backing it by gold is an entirely different story. As many nations grew to resent America’s currency advantage, countries around the world began to lay claim to their share of gold reserves, cashing in their unwanted U.S. dollars. This created a huge problem; namely, more demand for gold in dollars than actually existed in reserves.

The Nixon Shock

The gold standard effectively came to an end under the Nixon administration, when the government unilaterally cancelled the ability to directly convert the U.S. dollar for its equivalent value in gold. The move was touted as a hugely successful response to an exchange crisis caused by foreign meddling, so much so that markets like the Dow enjoyed their greatest gains ever, the day following the announcement.

Since then, however, we find ourselves back in a floating-fiat paper currency scenario that remains all too familiar. We have returned, once again, to a very recognizable stage in the ongoing cycle between real money—gold and silver—to paper currencies that are prone to over-production.

Inflation caused by excessive printing, and in some cases, hyperinflation in mismanaged or heavily sanctioned economies, is inevitable and ongoing, but not just regionally.

Now, the effect has become a global phenomenon.

The Digital Age

A coinciding global phenomenon is the digitization of currency. Often referred to as “cashless payments”, debit card, credit card and more recently, mobile payments, consisting of services such as Apple Pay, Google Pay, and PayPal, dominate daily monetary transactions and are particularly popular in the United States. In China, the WeChat Pay application is used by over 600 million people.

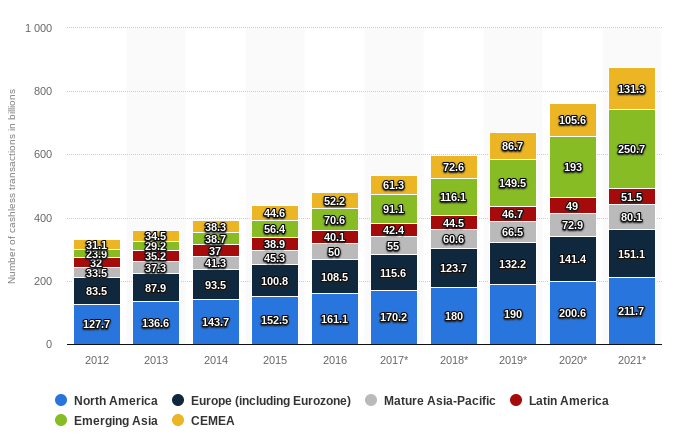

Cashless payments have ballooned over the past decade and are projected to accelerate worldwide. The following table displays global cashless transactions in billions by region from 2012-2016 with projections through 2021:

Like paper currency, these digital forms of payment are not inherently scarce and suffer from the same flaws as many currencies of the past, although they can be more convenient for a variety of scenarios.

The current state of near-cashless economies foreshadows a looming threat of falling interest rates, whereby currency users could be trapped in a continuously inflationary environment with no option to “cash out”. Such digitized currencies lack the capacity for monetary independence and privacy that is offered by cash, and especially by real money.

Bitcoin, Ultimate Real Money

Time and time again, we have seen throughout the world, a return to real money. Real money must be….

- A medium of exchange, used to trade for goods or services.

- A unit of account that is interchangeable and able to establish a set price for goods or services.

- Portable. More portable than any other form of currency, Bitcoin can even be stored in your mind via a 12 or 24-word mnemonic phrase.

- Durable. Being an immutable blockchain secured by massive hashrates, Bitcoin can not be destroyed without an enormous expenditure of energy and money.

- Divisible. Bitcoin can be divided to the 100 millionth, representing a single satoshi in value. It could be further modified by adjusting the protocol in the future, if necessary.

- Fungible, where each unit is the same as the next.

And, like gold and silver, Bitcoin is scarce, with only 21 million BTC that will ever exist, making it a store of value as hard money.

Although it is a digital iteration of money, it retains scarcity due to its protocol, thanks to the nature of blockchain technology. Bitcoin also uniquely retains the advantages of the age-old bartering system. It allows permissionless trade between parties and has no need for intermediaries in order to enable successful transactions.

It is the ultimate real money, superior to all previous forms, including gold and silver.

To fully understand Bitcoin’s superiority over all previous forms of money, we will continue this series next with a closer look at the gold standard and gold’s comparisons to Bitcoin in greater detail.

Share this article