Decentralization: The Big Problem For Blockchain

In a guest post, Gorbyte CEO Giuseppe Gori elaborates on the problems facing decentralized networks.

Decentralization is one of the buzzwords of blockchain technology: companies and web sites have sprung up that include this word as part of their name.

Decentralization has been touted as a most advanced feature in fintech.

But few realize that decentralization is itself the problem. This concept has kept blockchain technology stalled for many years.

Let me explain:

In the 1960s, computer systems were centralized, or configured as a star network. Only in the early 1970s did the need to connect computers from multiple manufacturers become urgent.

At the time, the nodes of the few existing communication networks were typically organized hierarchically, but from the very beginning the protocols implemented in the nodes of the ARPA, RPCNET, PISA and other groundbreaker networks preceding the internet were designed with the general idea that no central node or authority should control, lead, be the center of, or own the network.

In other words, we knew that a centralized, star, multi-tier network, with its innate bottlenecks, was not going to satisfy even the 1970’s requirements of thousands of users. We also guessed that by reducing the number of bottlenecks through decentralization the problem would be reduced, but not solved. We knew that a solution would have to use a distributed peer-to-peer model.

Since many organizations would be involved in the provision of nodes, links, possibly unreliable hardware and software, we had to assume that the network was unreliable. We did not know how a consistent set of data, or even a single transaction, could be maintained in multiple databases through an unreliable network when any node could generate a message or, in fintech terminology, a financial transaction. The problem was further compounded by the presence of deliberately malicious players.

Why blockchain technology has been hindered by decentralization

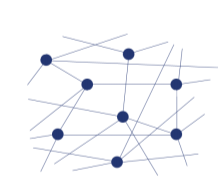

In general terms, we recognize that a network is decentralized when the control of the network is shared among a subset of the network’s nodes.

A network is distributed when all nodes equally share responsibilities and run the same node software.

Decentralized (permissioned and leader-based) networks were often extensions of centralized networks deriving from application requirements, for example by the fintech industry.

The blockchain network software (basic system software) should not be designed according application requirements, as these will change. We did not design the network precursors of the Internet and the Internet itself based only on the requirements of 1970’s applications. We could not have predicted what industries would develop based on the ability to share information globally.

In the same way, the underlying blockchain network should be as general, flexible and scalable as possible. The permissioned, client-server, and private network requirements can then be considered as special cases of a distributed network, for example by using the concept of Virtual Private (blockchain) Networks.

Distributed networks are more likely to be independent of any specific physical structure. Nodes can dynamically connect to each other and random connection procedures could possibly be used. Consensus solutions implemented on distributed networks can also be unpermissioned, majority- driven and recursive.

Distribution, not decentralization, should have been the main objective of crypto-network design.

Why we failed

The failure to investigate distributed consensus agreements partly derives from the 1982 formulation of the Byzantine Generals’ problem which models how information integrity can be maintained in an unreliable environment. The Byzantine Generals problem has been studied by researchers for over thirty years.

The analogy of several allied army divisions holding a city under siege correctly assumed that no-one in the field could be trusted to deliver a message and that some of the generals themselves could not be trusted when issuing a command.

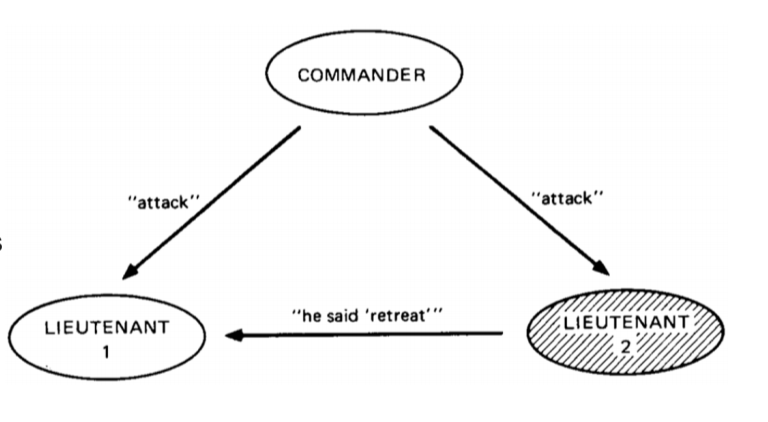

However, the formulation of the army analogy suggested at least two classes of troops: generals and soldiers.

Some people then restricted their thinking to a more specific case in which the generals issued commands that needed to be both carried to other generals and protected from tampering by attackers or traitors.

Eventually, this approach led to a limited definition of the consensus problem. Leader-based consensus models such as Paxos and Raft were and taught in universities and adopted as models by designers of implementations of blockchain networks.

As a result, practical solutions of the Byzantine Generals problem focused on various methods for selecting a leader node, which would send a block of verified information to all other nodes, instead of seeking to achieve a consensus on the content of the block.

Missing the target

A consensus on which node should be the current leader does not solve the problem of trust. The current leader must be trusted. It must do the job of verifying and assembling blocks in a fair manner. Thus, the leader in current leader-based consensus protocols is required to provide some credentials: proof of work, proof of stake, proof of capacity or proof of anything else.

These “proofs” do not guarantee much more than a vested interest that leader nodes (or nodes aspiring to be leader nodes) may have in the network: the more interest they acquire, the less they will be willing to destroy their form of income.

These “proofs” guarantee that potential leaders have credentials, but do not guarantee that the information assembled in the block is correct, or at least that it has been verified by a majority of the nodes.

We have seen more than 60 proposed solutions based on leader-based models for various blockchain implementations. They suffer from a common fault: one node decides what every other node will store on the blockchain. The result is almost the opposite of what is required.

Summary of the disadvantages of leader-based protocols

Leader-based protocols have the following disadvantages:

- They do not solve the problem of trust. The leader node may introduce faulty data, intentionally or not, in the block of information.

- Rewards, associated with the work of verifying and assembling blocks, create an incentive for nodes to compete for the rewards and to be promoted to leadership positions. This incentive tends to create a special class of nodes. The network then morphs into a decentralized network. For example, Bitcoin started as a network of peers where every node could verify transactions and compete for a reward. Today it is a two-class network (miners and users) and is controlled by large pools of owners.

- When the assembly of a block is left to one node, one of the major requirements of consensus theory is invalidated: the agreement is not based on a majority consensus about what information will be stored on the blockchain. The only agreement reached is the method for choosing a leader node.

- A bottleneck, or single point of failure, is introduced: One node has to broadcast a block to every other node.

- Efficiency is not the best: large blocks of data are more subject to transmission errors and re- transmissions of maximum size packets.

- Redundancy is almost 100%: Each transaction included in a block has already been received by every node separately, when the transaction was initially issued.

A better analogy

When thinking about an analogy for the problem of reaching a common decision in an unorganized and unreliable environment, we could have used an analogy of an army without ranks, but it would not have been very intuitive.

A better analogy could have been the challenge of deciding the daily closing price on a stock exchange. In this analogy, a multitude of buyers and sellers determines the daily closing price of stocks using a stochastic process, without any particular person taking a decision for anyone else.

In the stock market there is no “right” answer for a stock price, but just an agreed daily closing price.

Similarly, in the composition of a block several variables, such as the order of the transactions, can determine the final block composition. There is no “right” block composition, but just one that nodes agree on.

Consensus protocols based on a more distributed analogy could have avoided the tendency towards centralization and the requirement of intermediate nodes, typical of leader-based protocols.

Examples of intermediaries in a network are:

- Miners, producers or verifiers, volunteering or engaged to provide a service to the network,

- Special nodes of federated systems that have a stake in the success of the network,

- Nodes elected with some criteria to perform network governance,

- Nodes owned by trusted companies or institutions,

- Special players, such as centralized Currency Exchanges holding user wallets.

What’s wrong with Intermediaries?

First of all, it is a question of cost: If the intermediaries are doing useful work, for example verifying transactions, then they need to be rewarded.

It is also a question of trust: customers using a network with intermediaries need to trust:

- that the intermediary is not giving preference to certain users or transactions,

- that the intermediary has not been, or will not be, taken over by a malicious attacker,

- that the intermediary’s system is not experiencing a blackout, or targeted by a DoS attack, or experiencing a system failure, or any other cause that will affect or delay customer transactions,

- that intermediarys’ system software and data are reliable, so that data integrity and security are guaranteed.

- that they are really connected to a trusted system and not to an impersonator (e.g., some other system pretending to be a trusted intermediary), and

- that no other unpredictable event will happen. Recently, for example, the owner of the Canadian currency exchange Quadriga died or disappeared. As a result millions of dollars of customers’ funds are missing.

Finally, it is a question of data availability. If a network has a privileged or restricted class of nodes managing the blockchain, then the majority of nodes do not have immediate access to the current replica of the blockchain. This may preclude the development of real-time applications, such as automated trading applications.

Is it too late to change the model for blockchain consensus?

Most experts will tell you that a major function of consensus protocols is to maintain the security of the network. This view confuses two issues. Security is certainly needed, but it is a completely different requirement that can be solved by other means (and this will be the subject of a separate article).

Still, many developers are stuck with the ideas that consensus means choosing a leader and that consensus is needed to maintain security.

With hind-sight, if we had thought of a better distributed analogy, the research could have turned towards a different direction, suggesting stochastic approaches and possibly could have led us to the earlier development of better distributed solutions without intermediaries.

This is now an education issue, more than a technical issue. Most researchers, consultants and experts on crypto-networks are proficient in all the details of PoW, PoS, DPoS and several dozen alternatives, all based on the same leader-based model. The few solutions that are not leader-based, are not blockchain solutions: They are solutions in which each transaction is handled separately.

On the positive side, most people and 95% of companies, according to a recent poll, understand the potential of blockchain technology.

A transition, from a de-centralized to a distributed model, is urgently required to unlock the blockchain’s true potential, to solve the problems of scalability and to run the blockchain on any user device without intermediaries.

Crypto Briefing does not accept any payment or financial benefit from expert guest authors.

If you are a blockchain expert with an interest in sharing your knowledge and experience, please contact our Managing Editor, Jon Rice, via email at editor AT cryptobriefing.com