How to Report Bitcoin Forks and Ethereum Airdrops on Your Taxes

The advent of blockchain technology has created new, complex tax situations. Here's how to report Bitcoin forks and Ethereum airdrops on your taxes.

The advent of Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other cryptocurrencies has introduced unprecedented ways to distribute new assets, creating complex tax situations. Here’s how to account for forks and airdrops, and a few strategies to minimize taxes.

There is little precedent when it comes to taxes around forks and airdrops.

“In the traditional world, nobody airdrops anything. The dollar doesn’t fork every Tuesday,” said Alon Muroch, CEO of crypto accounting platform Blox, in an interview with Crypto Briefing.

Ruling from other regulatory agencies adds to the complexity. By the letter of the law, many cryptocurrencies are not considered money, or commodities, but instead securities—investments that represent a contract between a buyer and an enterprise.

“You should start with the assumption that you’re starting with a securities offering,” said SEC Chairman Jay Clayton. Failing this assumption, or misinterpreting the rule of tax law, has led to “a majority of companies filing incorrectly,” LukkaTax’s co-CEO, Robert Materazzi, told Crypto Briefing, who claims that most portfolio apps that link to a tax service are doing so incorrectly.

FinCEN has issued its own guidelines around money transmitter rules for cryptocurrency, treating crypto like cash for anti-money laundering purposes. Meanwhile, the Commodities Future Trading Commission treats Bitcoin as a commodity. The U.S. Internal Revenue Service treats it as property. Ethereum falls somewhere in the middle.

Between the regulators, it’s one confusing mess of three and four-letter acronyms giving mixed messages.

What Is a Blockchain Fork?

A fork is a software change that creates two separate versions of the same blockchain. Most often, forks are used to introduce upgrades, where the old version of a blockchain is replaced by the new one as soon as the fork is executed.

Occasionally, however, forks are used to settle disagreements over technical features, like the block size debate that lead to Bitcoin Cash. Other times, it’s about governing philosophy, like in Ethereum Classic. Yet other times it’s about taking advantage of a brand name, like Bitcoin Diamond. They’re an integral part of what makes a decentralized blockchain, well, a blockchain.

Forks happen all the time. Since inception, Bitcoin alone has had over 50 forks.

To make matters worse, holders often aren’t aware that a fork has even taken place and many coins go unclaimed. Nevertheless, the IRS views forks as taxable events.

Understanding Token Airdrops

Airdrops are another situation where money falls out of thin air. In an airdrop, coins are “carpet bombed” to thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of cryptocurrency addresses as part of marketing campaigns, said Muroch.

One example of a massive airdrop was the one executed by Stellar, a cryptocurrency created by XRP co-founder Jed McCaleb. In September of last year, the Stellar Foundation announced it would airdrop 2 billion XLM, worth over $120 million at the time. An unprecedented sum.

Again, like forks, the owner of a cryptocurrency address that benefits from an airdrop is often unaware of the windfall. Many times they do not even consent to receiving an airdrop.

“You’re not always aware that you receive assets from a fork. You can couple that with airdrops, not just forks,” said Muroch. “All those holders had taxable events because someone in the marketing department decided to use that as a marketing tool.”

Tax Implications of Forks and Airdrops

Consent aside, the IRS has voiced its position on forks and airdrops. “The receipt or transfer of virtual currency for free, including from an airdrop or following a hard fork,” needs to be reported for tax purposes, says the IRS.

The power to collect taxes from these events, even crypto, come from broad powers given to the government over a century ago. “The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived,” reads the 16th amendment.

The IRS has offered some clarity concerning the confusion. In October 2019, the agency issued a ruling on the issue.

Crypto holders recognize income when they “exercise dominion and control over the cryptocurrency” received through a fork or an airdrop, according to the rules. That is, when a holder gains the ability to transfer or sell the cryptocurrency.

Wendy Walker, a tax withholding and reporting expert at Sovos, a tax reporting software company, reaffirmed this position in a conversation with Crypto Briefing. Forks are treated as “ordinary income,” and the specific amount of tax liability would depend on the valuation scheme the taxpayer is using, she said.

By default, coins are valued using the FIFO, or “first in first out,” method of accounting, where the oldest units of cryptocurrency are used to determine the cost basis, said Jim Calvin, a tax partner at Deloitte.

Though there are other valuation methods that may produce less tax liability, like LIFO or average cost, and these are viable so long as they are consistently applied. If this all seems confusing, an example might help illustrate the tax implications.

Using the Bitcoin Cash Fork as an Example

Bitcoin Cash split from the Bitcoin network on Aug. 1, 2017, to settle a disagreement over the block size, which essentially determines the upper limit to how many transactions can be processed by the Bitcoin network in a roughly a 10 minute interval.

Those who held their private keys prior to the chain-split received a number of BCH equal to the number of BTC they held.

Bitcoin was trading at $2,800 the day of the fork. Immediately after the split, Bitcoin Cash opened on exchanges at $290. A taxpayer who had received BCH would recognize $290 in income, which would also determine the cost-basis of the BCH.

Later the next day, if the taxpayer sold their Bitcoin Cash when it was trading at $380, they would recognize capital gains of $90:

$380 - $290 = $90

Hypothetically, if the price of Bitcoin dropped as a result of the fork, it might be possible to offset some of the income from the fork, but the rules around this are unclear.

Tron’s Ethereum Airdrop as an Example

Another example to demonstrate the recognition of income is when Tron airdropped 30 million TRX to Ethereum holders. Announced April 2018, Ethereum addresses with a balance of one or more ETH received between 10 and 100 TRX.

TRX was trading at $0.5 on the day of the airdrop, April 20, 2018. Assuming an address received 50 TRX, the Ethereum holder would recognize income of $25 on that day ($0.5 x 50).

To illustrate the impact of FIFO, if those coins were received over a series of days (from the 20th to the 22nd, for example), then the following accounting would take place:

April 20: 50 TRX at $0.5 each ($25) April 21: 50 TRX at $0.6 each ($30) April 22: 50 TRX at $0.7 each ($35)

In all, the account holder received $90 worth of TRX, and would recognize this sum as revenue. Hypothetically, if they sold 60 TRX at $0.7, they would recognize gains from the oldest batches of coins first under FIFO.

The April 20 batch as the “first in” would get sold first, for reporting purposes. The 50 TRX with a cost basis of $0.5 each and sold for $0.7 each would register a gain of $10:

(50 x $0.7) - (50 x $0.5) = $10

Then, it would take 10 TRX from the batch from April 21, which were obtained at $0.6 each:

(10 x $0.7) - (10 * $0.6) = $1

In total, the taxpayer would recognize capital gains of $11, in addition to the $90 of income from the three batches of airdrops.

In some circumstances, especially for those who trade often, it can be advantageous to use the LIFO method which takes the newest coins first, allowing some of the coins held for more of the year to get preferential long-term capital gains treatment.

Issues Raised by Airdrops

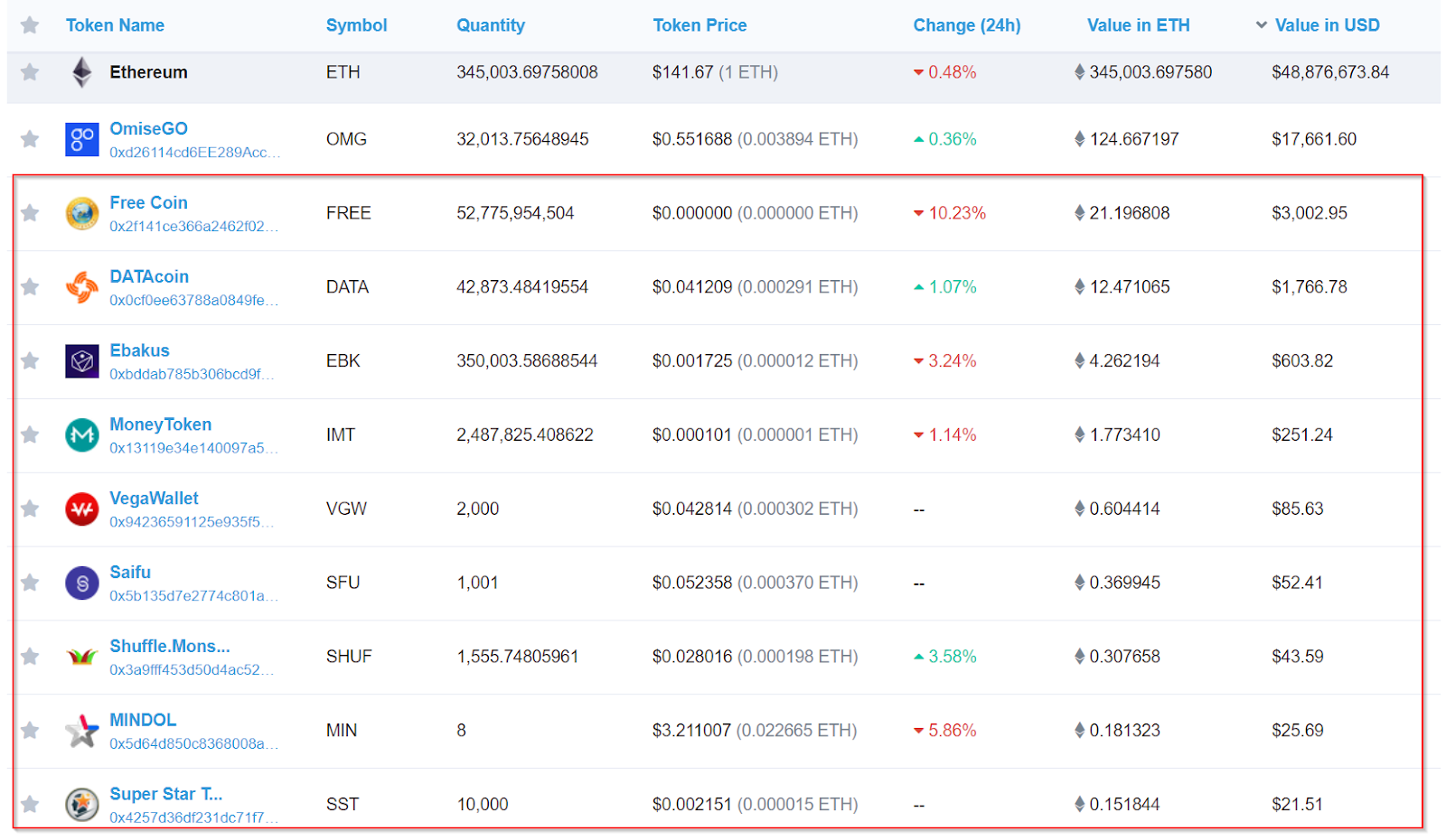

Airdrops are an issue for holders of Ethereum and other smart contract blockchains. Even if the owner of the address did not consent to receiving the tokens they would still incur tax liability. Oftentimes, Ethereum holders receive hundreds of unsolicited tokens at no fault of their own.

Looking at Vitalik Buterin’s wallet address as an example, he has received over a hundred unsolicited airdrop coins worth thousands of dollars.

If the rules are to be followed by the book, each and every one of these airdrops would be recognized as revenue on the date of receipt. Further complicating the issue is that many of these coins are not traded on reputable exchanges, meaning their prices are unreliable.

In the end, this results in an accounting headache and an unwanted tax liability for holders of Ethereum, Tron, EOS, and other smart contract coins.

IRS Ramps Up Crypto Enforcement

These tax agencies mean business. Regulators are well aware of cryptocurrency’s role in aiding tax evasion and money laundering. Those who think they can get away without paying taxes are at risk of an audit, along with steep penalties.

Transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain are public, for the most part. It’s only a matter of time before the IRS is able to trace these transactions back to taxpayers, Walker told Crypto Briefing.

More alarming is that more than 50% of CPAs expect that at least half of their clients will be audited for back taxes on their crypto holdings, according to a joint report by Blox and Sovos. Reputable exchanges report activity from crypto traders to the IRS. Coinbase, Kraken, Binance.US, and Gemini all disclose this information to tax agencies, making evasion difficult.

In June of last year, the IRS mass mailed targeted letters to taxpayers suspected of “misreporting” cryptocurrency transactions. British tax authority HM Revenue & Customs has issued similar warnings.

“Cryptoassets like Bitcoin have attracted a lot of interest from people who are new to investing and have probably never filed a tax return in their life. It’s really important for investors to start doing the maths now so they know how much profit they’ve made and the tax due,” said Iqbal Gandham, UK managing director of eToro.

These authorities are serious, and it’s likely they’ll continue to crackdown on those intentionally and unintentionally underpaying on their taxes.

Caveats and Strategies Around Cryptocurrency Income Recognition

There are, however, some caveats. Exchanges don’t always immediately recognize forks as tradable assets, and many do not register airdrops at all. This can be used to the taxpayer’s advantage.

Coinbase, for example, did not offer support for BCH for a full four months after the fork. As a result, holders wouldn’t recognize income until they could “exercise control” over the asset. That is, until they could transfer and trade it.

So, for those trading on Coinbase, income wouldn’t be recognized until that date, when Bitcoin Cash was worth over $2,500 per coin (instead of $290 per coin).

This fact can be used as a tool to reduce tax liability. By storing coins on an exchange, a holder can avoid getting bombarded by airdrops, which would normally trigger taxable events.

To take advantage of this, an investor could store coins on an exchange and wait until their income drops to claim those coins (supposing they waited until they could offset their gains by selling some coins at a loss, or expected less income in a coming tax year).

How to Report Forks and Airdrops on Your Taxes

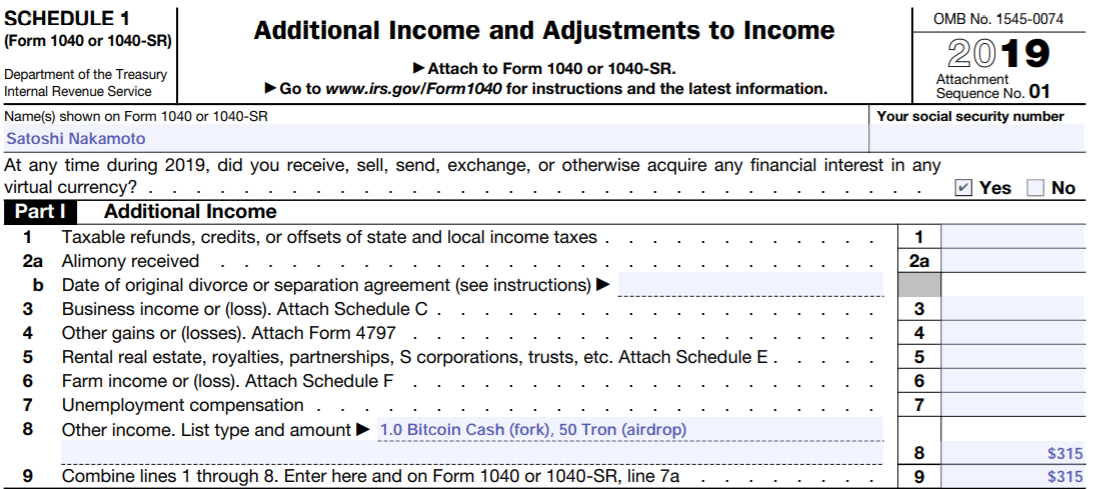

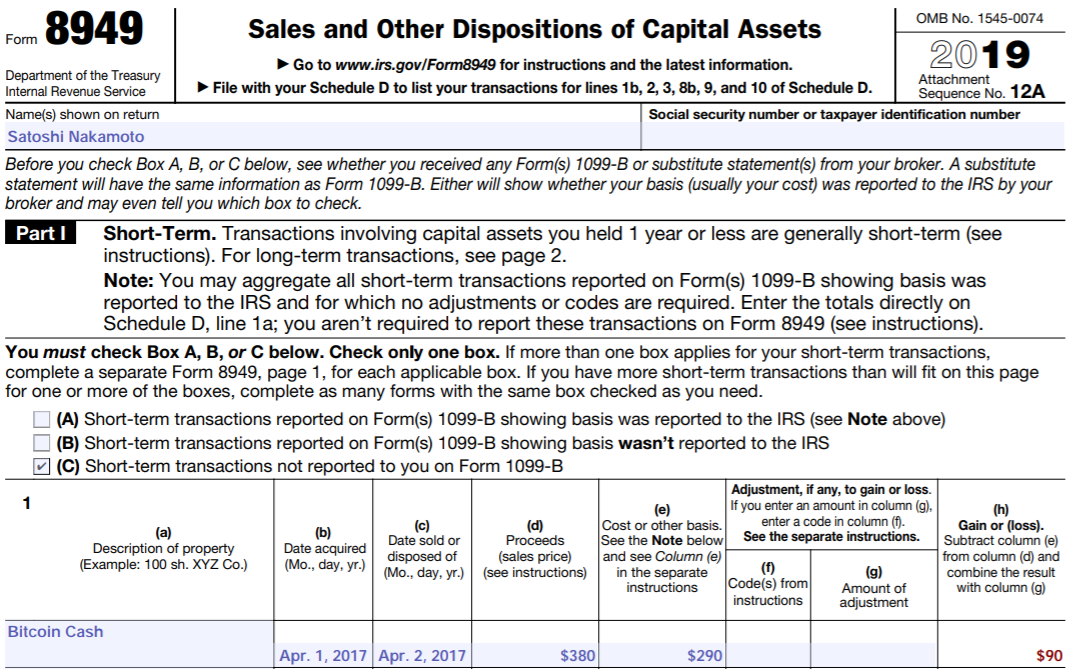

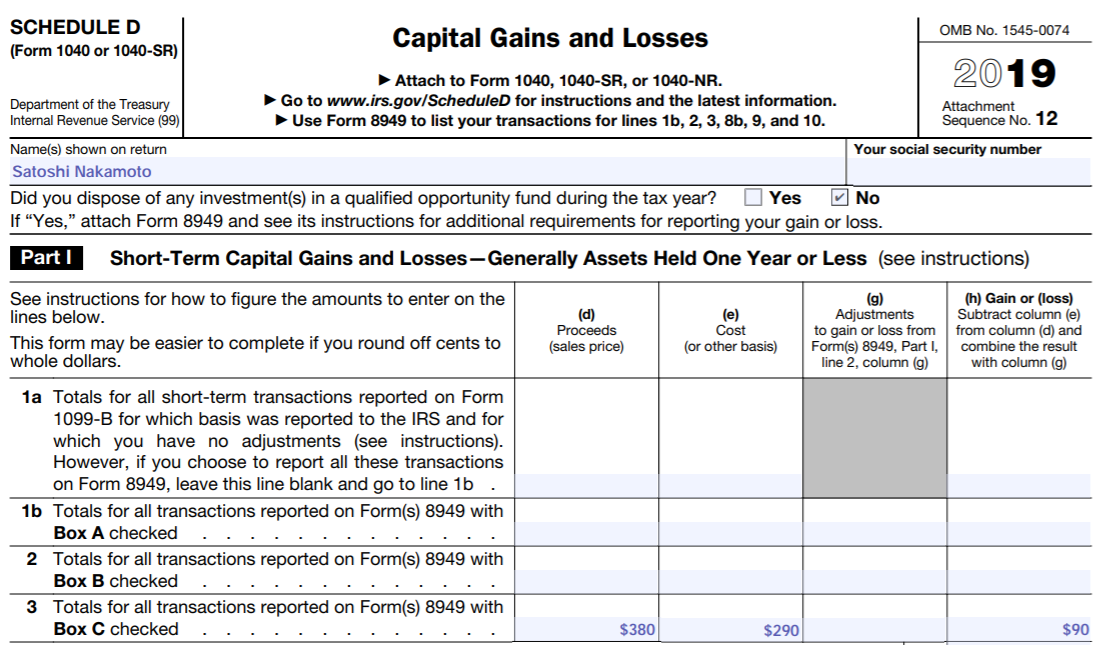

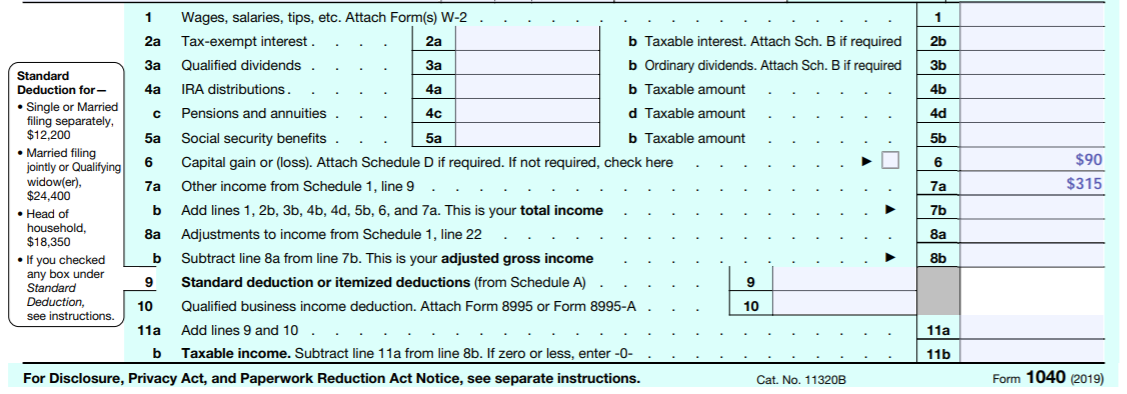

In sum, here’s how to report forks, airdrops, and capital gains on a tax return. The following exercise uses the Bitcoin Cash fork and Tron airdrop from the earlier examples. The entire process requires four different IRS forms.

These include the following: the 8949: Sales and Other Disposition of Capital Assets, the Schedule 1: Additional Income and Adjustments to Income, the 1040, Schedule D: Capital Gains and Losses, and the 1040: Individual Income Tax Return.

- Assuming the taxpayer received 1.0 Bitcoin Cash from the fork and 50 Tron from the airdrop in the earlier example, first fill out the Schedule 1 as follows:

($290 x 1 BCH) + (50 TRX x $0.5) = $315

- Then, for the capital gains associated with the sale of the Bitcoin Cash, itemize each sale and report it on form 8949. For those who trade regularly attaching a spreadsheet can greatly speed-up the process.

(Sale price: $380) - (Price at fork: $290) = $90 gain

- The sum of these cryptocurrency sales are then reported on Form 1040, Schedule D.

- Finally, input these figures on the 1040 form with all other sources of income:

(Capital Gains: $90) + (Fork and Airdrop Income: $315) = $405 total income

Between the fork, the capital gain, and the airdrop, this taxpayer would have $405 in additional total income.

At first glance, it may seem that reporting tens and sometimes hundreds of cryptocurrency transactions would be daunting. It is, without the aid of spreadsheets or software.

But, with enough diligence, it’s possible to report these transactions yourself. Beyond that, those who plan in advance can even reduce how much they owe, allowing them to keep more of their hard-fought gains.

For more information on proper filing, refer to official guidance from the IRS and their frequently asked questions guide.

The information presented here does not represent tax advice. Please consult with a professional before making decisions about your taxes.