Circle's new crypto

Did The Fed Really Just Print Money Out of Thin Air?

Despite what Powell said, the Federal Reserve did not literally print money to helicopter into the economy.

How accurate is the narrative that the Fed is simply printing money out of thin air to pump into an at-risk American economy?

“Yes. We Did.”

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell shocked many when he answered CBS’ Scott Pelley’s question “Fair to say you simply flooded the system with money?” in a 60 Minutes interview with “Yes. We did. That’s another way to think about it. We did.”

The Chairman went on to say:

“We print it digitally. We as a central bank have the ability to create money digitally and we do that by buying Treasury Bills or bonds or other government guaranteed securities. And that actually increases the money supply. We also print actual currency and we distribute that through the Federal Reserve banks.”

It is important to remember, however, that markets hang on every word the Fed says. Powell’s intention was to calm market nerves by signaling that the Fed printed money.

To the crypto community, the idea that a central bank can simply print money out of thin air was both alarming and a welcomed justification for hard, or fixed cap, money that prevented a central authority capable of debasing it.

And so, the money printer go brrrrr meme was born. Crypto had found its moment of legitimacy.

But Did The Fed Actually Print Money?

The key to understanding the Fed’s actions in response to the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic is twofold.

Firstly, the Fed creates the vast bulk of its money digitally. Secondly, and more importantly, the Fed can purchase assets from the government and place them on its balance sheet.

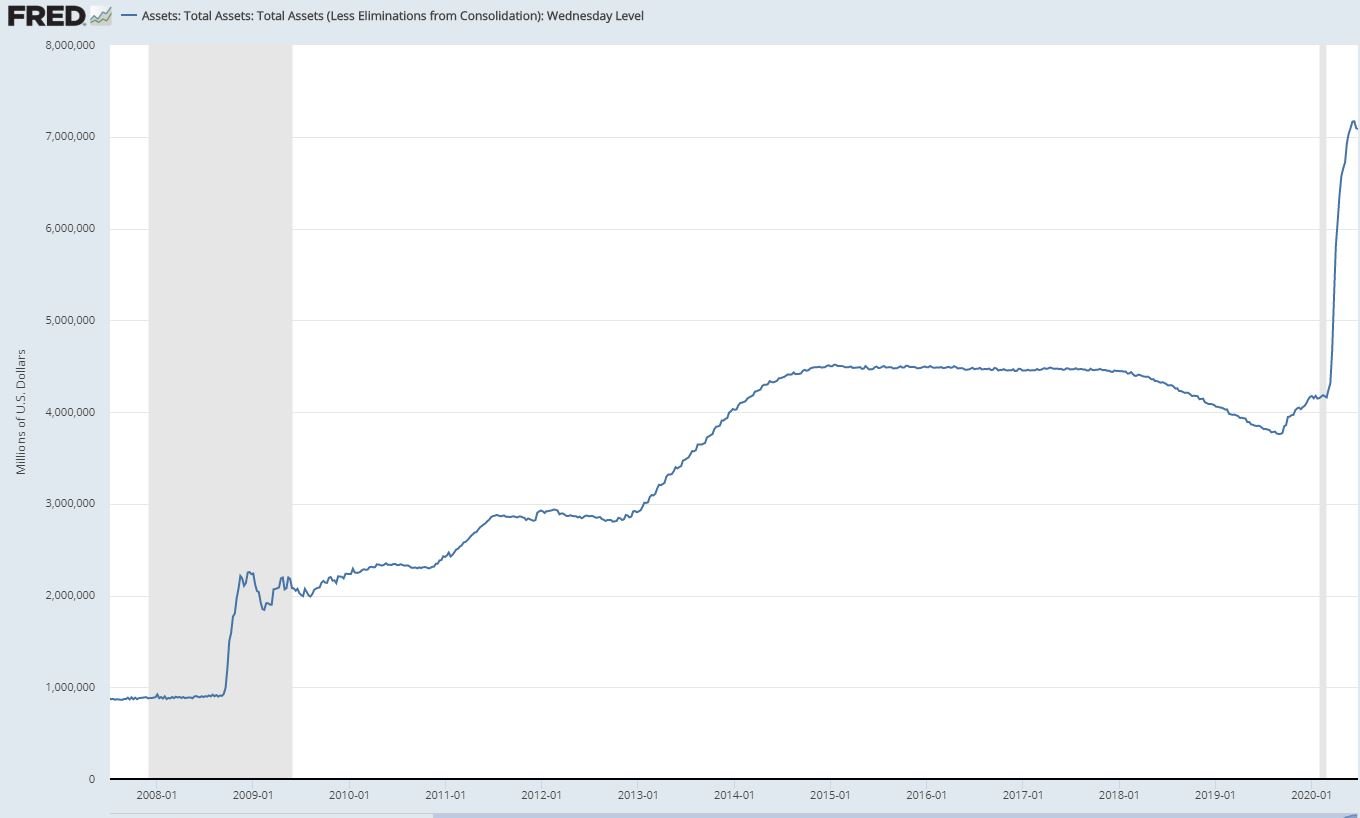

The total assets on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet have ballooned this year, as the chart below illustrates.

Importantly, the Fed has an unlimited balance sheet. It can buy as many government securities as it wants to shore up weaknesses in the economy. It plans to use these powers to bail out precariously placed investors and absorb Congress’ stimulus packages.

The Fed intended to adjust interest rates and encourage lending. Bank lending is actually the primary driver of money supply in a modern economy, and incentivizing lending plays a vital role in the Fed’s mandate to “promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long term interest rates.”

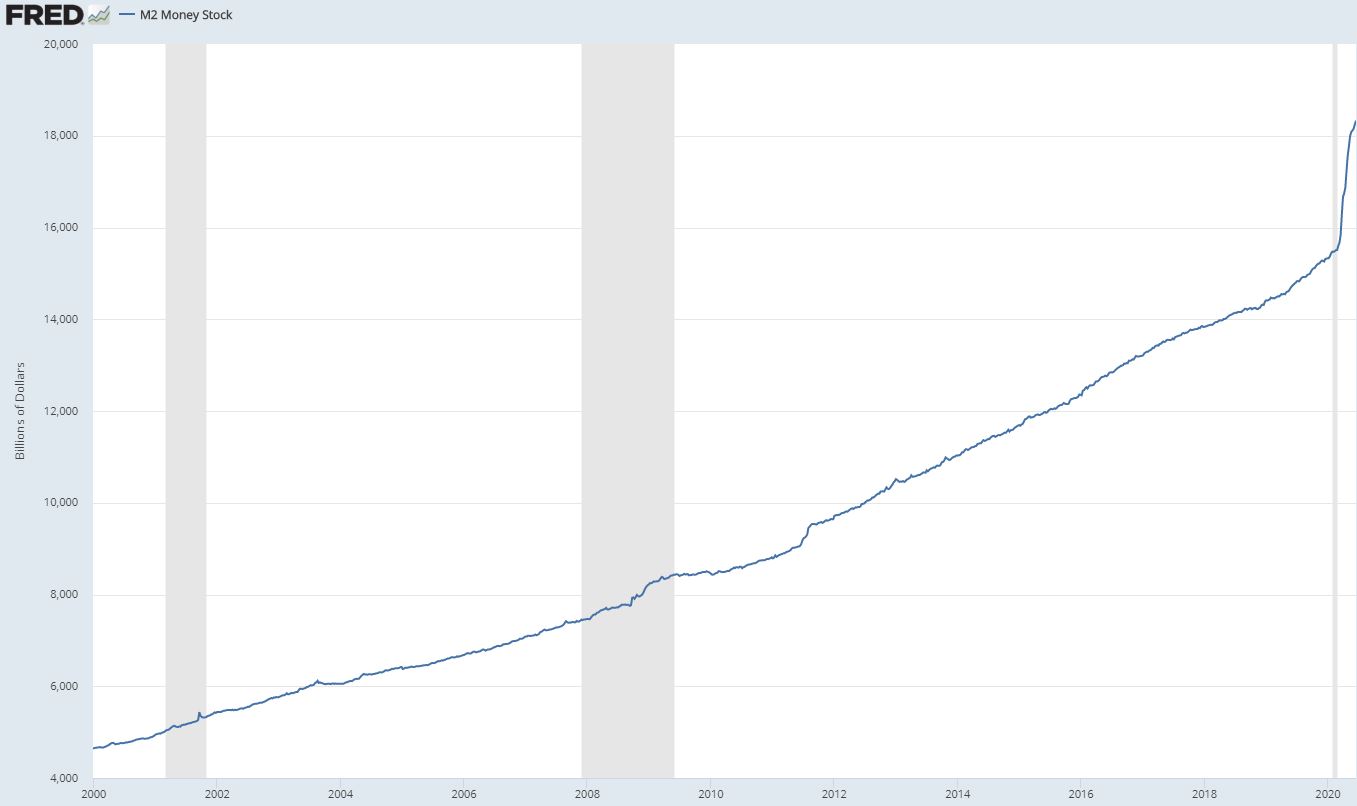

To measure the money supply, financiers refer to M2 as an accurate metric.

M2 includes M1, money in circulation and checkable deposits in banks, as well as savings deposits and money market mutual funds.

The Fed makes no direct impact on M2. It aims to reduce interest rates to encourage lending. That results in the indirect – albeit intended – expansion of M2.

The expansion of M2 above is the product of the government’s emergency fiscal programs. The government can do that because, with an unlimited balance sheet, the Fed can use quantitative easing programs to expand the monetary base.

The graph below indicates the expansion of the base, which preceded and enabled the expansion of M2.

The central bank’s quantitative easing programs expand the monetary base, but that money remains as reserves. It is then up to market participants to engage in more lending and borrowing – at cheaper rates – to enhance economic growth and stability.

Long-Term Consequences

The potential long-term consequences of Fed largesse are asset bubbles, excess inflation, and the propping up of so-called “zombie companies.”

But perhaps the most insidious consequence is the exacerbation of income inequality that follows monetary easing, known as the Cantillion Effect.

The Cantillion Effect means that the asset bubbles impact those who can least afford it. Those at the insertion points of liquidity into the economy that result from quantitative easing are well-placed to purchase assets before the ensuing inflation.

By the time the money reaches those most marginalized, inflation has already occurred, forcing them further toward the economic fringes.

Nobody could dispute the need for intervention during the economic shock caused by COVID-19. But if the GFC is any indication, central bankers cannot be trusted to restore economic neutrality when their response is no longer needed.

Furthermore, the Cantillion Effect makes the Fed’s quantitative easing programs far from benign. Short of unlikely redistribution policies once the economy is in recovery, the marginalized will increasingly be so.

The Fed does not print money, physically or digitally, to pump into the economy during a crisis.

Instead, it expands its balance sheet by buying assets, which results in the expansion of M2 and lower interest rates. The language Powell has used is intended to shore up market confidence during times of uncertainty.

Nevertheless, the Fed’s recent history of keeping interest rates too low for too long and being mostly unable to stimulate significant growth, suggests the COVID-19 response will become yet another argument for a hard currency like Bitcoin.

Earn with Nexo

Earn with Nexo