EOS Ecosystem Dying: BP Collusion, Community Fragmentation, High Costs

Despite raising $4.1 billion during its ICO, EOS hasn’t been able to unseat Ethereum. Studying the network’s shortcomings provides a unique case study on how money can’t buy adoption.

EOS conducted one of the largest ICOs in the crypto space, attracting almost half of what was invested in all offerings during 2017, and for good reasons.

The network boasts enticing technology that, on paper, outdoes Ethereum at scalability and ease of development. Moreover, EOS-based dApps don’t ask users to pay for transactions, making them more friendly than expensive Ethereum-based dApps.

So, if EOS solves Ethereum’s major issues, why hasn’t it taken the lead?

It turns out, sound technological concepts and deep pockets aren’t the only features that attract vibrant communities of developers and users.

While EOS was able to bootstrap a community at its launch, it failed to retain it. The platform’s high centralization and prohibitive usage costs have forced many to create forks and migrate elsewhere.

The project needs a strategic approach to its ecosystem development to stop stagnating and start growing.

The EOS Oligarchy

Discussions between EOS block producers (BPs) and Crypto Briefing revealed that the network was initially supported by a grassroots movement, a healthy characteristic for any public blockchain. However, as the stakes increased, large players joined and took over EOS governance.

Unlike Bitcoin and Ethereum, EOS utilizes the Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS) consensus. The “Delegated” part played a significant role in the formation of the network’s current oligarchy.

Only 21 nodes can produce blocks and therefore earn block rewards. The incentive to join the coveted block production committee creates competition, which theoretically is beneficial for the network overall. However, in practice, there are some complications.

The election of BPs is based on how many votes each candidate receives. And as each vote has a price, nodes with deep enough pockets can game the system, prolonging their reign on the block production committee indefinitely. It’s a common issue of DPoS platforms that projects like IOST have tried to solve.

With the advent of services like GenPool, it has become even harder for new players to enter the block production committee. Such services incentivize users to support the top-positioned nodes to maximize rewards.

The EOS constitution prohibits gaming the system for profits, but with no enforcement. The constitution, designed to prevent this kind of governance capture by block producers, has no impact on the network. EOS Core Arbitration Forum (ECAF) should have become the enforcement branch, but it failed after the community’s backlash.

Moreover, besides an on-chain oligarchy, EOS shows signs of having an off-chain one too. For instance, in 2019, one of the block producers, EOS New York, revealed that a single entity registered six BPs.

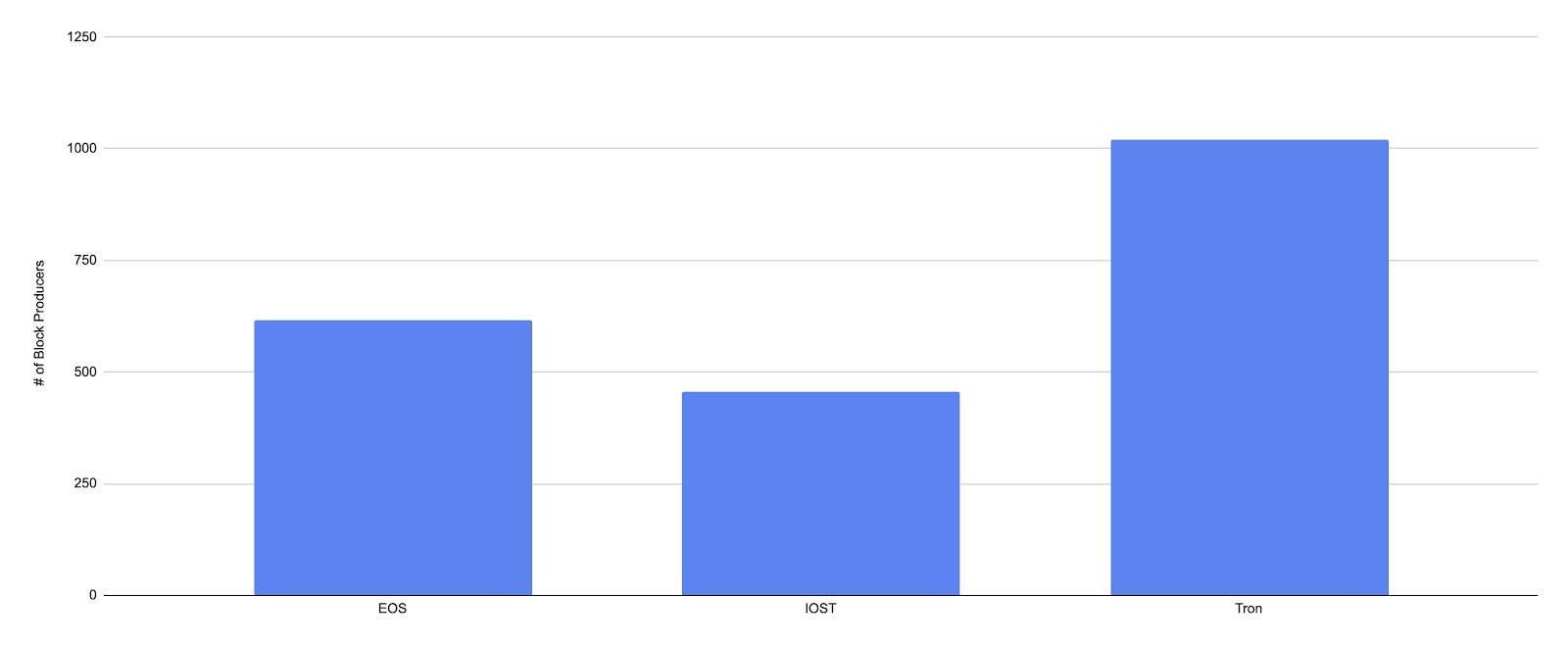

Since EOS is dominated by several large players, it isn’t appealing for smaller node owners. The platform has over 40% fewer nodes than its closest competitor, Tron.

Expensive to Build On EOSIO

Like BPs, developers of decentralized applications (dApps) feel unwelcome on EOS.

Interviews conducted by Crypto Briefing showed that while EOS technological stack and tools are convenient for building applications, deploying them is expensive due to the high price of computational resources on EOS.

One of the key challenges all application developers face is user onboarding. When it comes to signing on new users, EOS has a better user experience than fee-based platforms like Ethereum. There is less friction for new users because they don’t have to create wallets and top them up in advance.

EOS developers eat the cost of onboarding new users. In line with the EOS architecture, deploying a dApp requires renting resources like CPU and NET, and buying RAM. If the dApp user base increases down the road, more resources need to be allocated by developers.

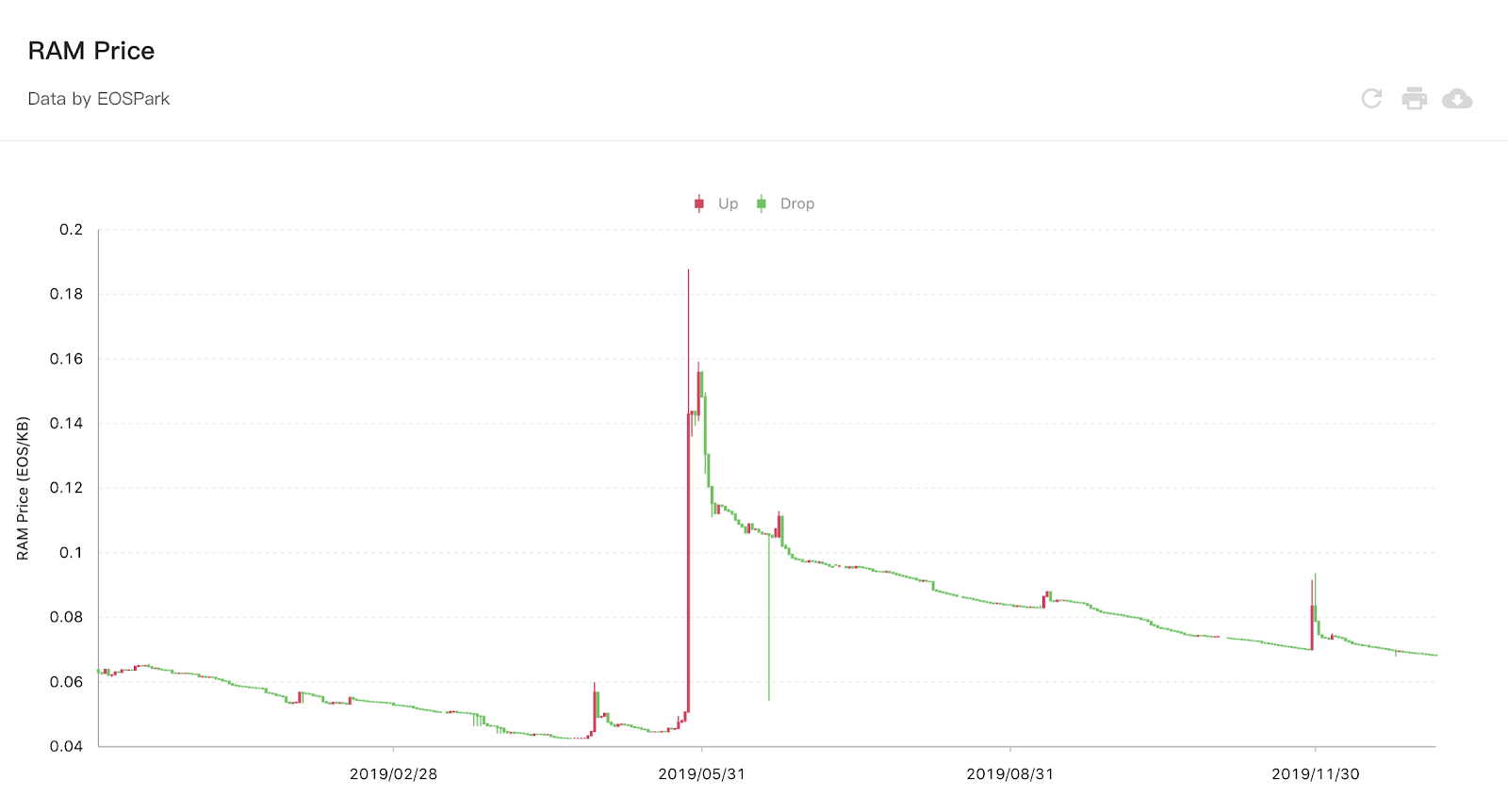

EOS resources create secondary markets, which can be skewed by speculation. For instance, RAM prices can spike, which can hamper dApp development. At the current EOS and RAM prices, buying storage per account comes out to just under $0.9, which is very expensive for dApp deployment. For instance, scaling Voice on EOS to a size of Facebook would require paying over $2 billion just for creating accounts.

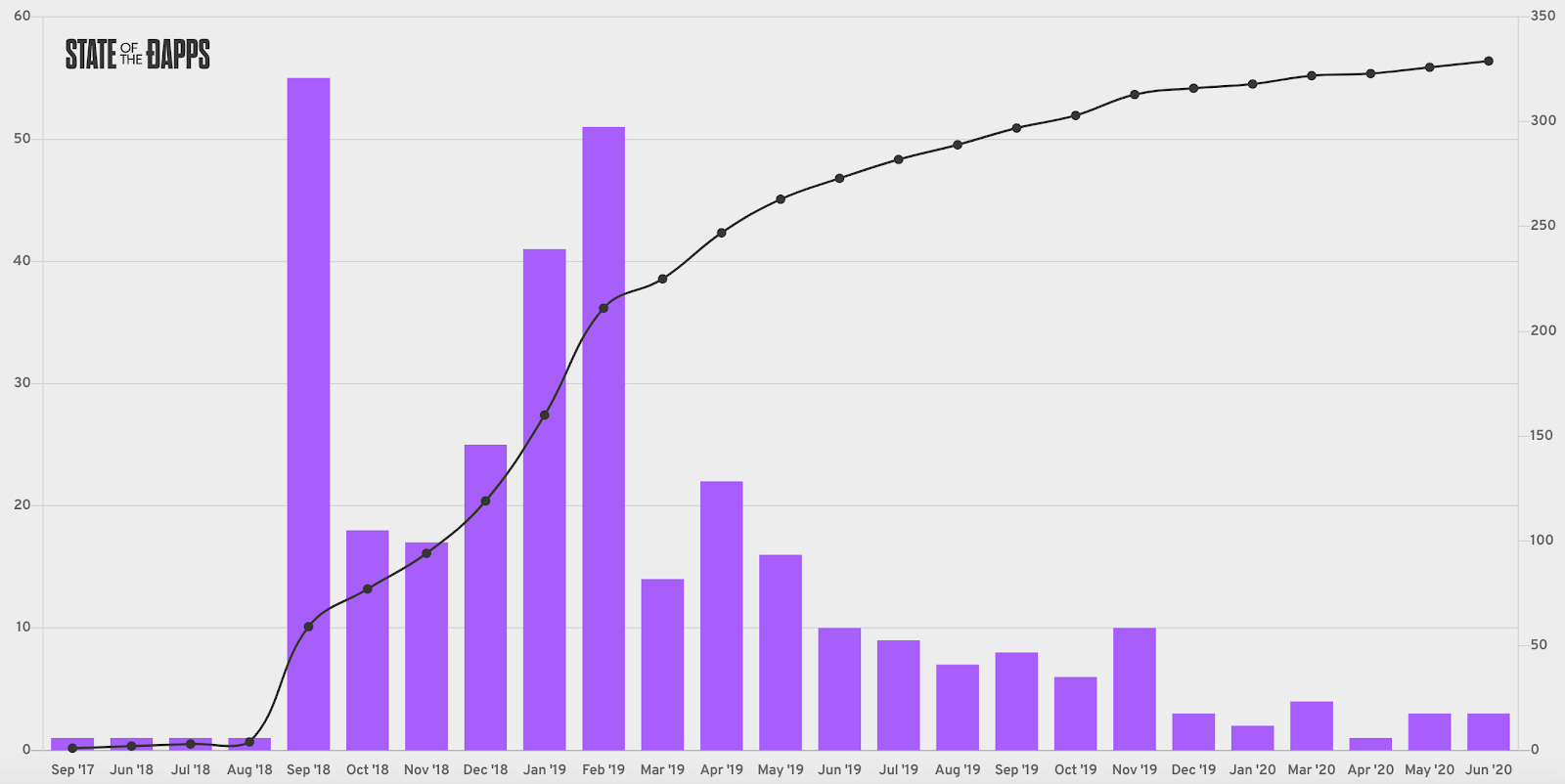

Prohibitive development costs led to a decline in new dApps on the platform. In July 2020, only one new dApp appeared on EOS, compared to 32 on Ethereum.

EOS Community Fragmentation

EOS oligarchy and its high cost of development have pushed many community members to take the underlying technology and build alternatives. Consequently, a range of network forks, including Telos, WAX, and Boscore emerged.

The platform’s forks are sucking away its developers and users. For example, in 2019, WAX conducted a campaign that financially incentivized dApp developers to relocate their products. In slightly more than a year since inception, WAX was able to bootstrap a sizable community.

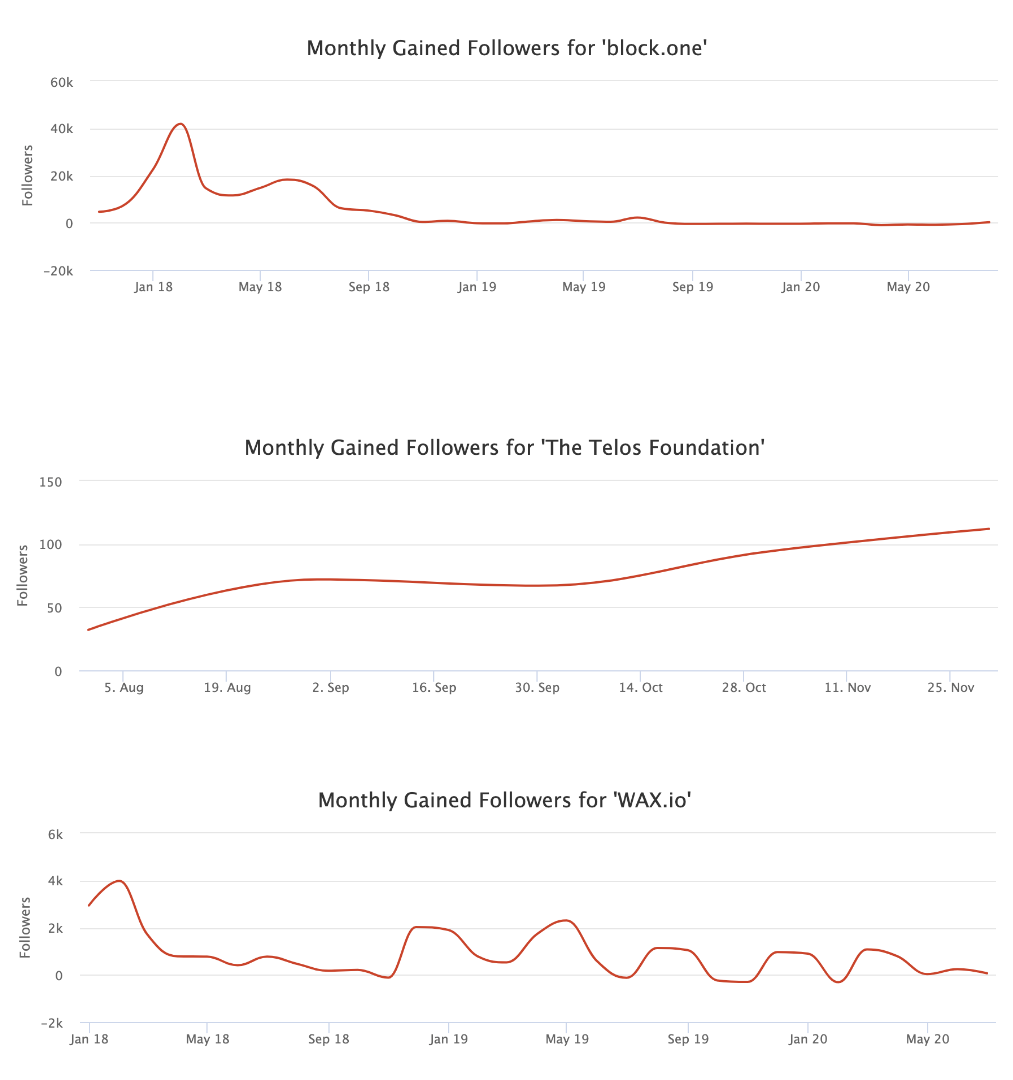

Social media activity shows that more users are paying attention to these EOS forks, while the main network loses its follower base.

The current dynamic is thus more conducive to a mass splintering in which various EOS forks scatter and compete in a zero-sum game for users. Over the long-term, this splintering will slow the development of the broader ecosystem as network effects will never reach critical mass.

That said, Douglas Horn, the architect of the Telos blockchain, does offer a counterpoint:

“It’s more accurate to view this entire ecosystem as one where chains both compete and cooperate and in that process accelerate development. The fact that dApps will migrate between chains is an overall strength because it means that they will never be marooned on a fading platform or one where costs spiral out of control. It means that no chain can coast on development or it will be outpaced by others,” he said in a conversation with Crypto Briefing.

Can Block.one Fix the Problems with EOS?

During a critical period when developers and users need a comprehensive expansion strategy, Block.one’s focus is elsewhere.

Block.one conducts hackathons, invests in developers, and distributes grants, which can bring more developers into the ecosystem, but it doesn’t solve its high costs. So even if new teams come to EOS, they may be inclined to migrate to one of the platform’s cheaper forks.

Meanwhile, Block.one claims that “the operating cost of running an EOSIO network is akin to that of maintaining a traditional server.”

Some of the initiatives, like EOS Labs, a GitHub repository intended to foster open source development across the project’s community, are positive. However, given the existing roadblocks for individual developers and node owners, it’s unsurprising that the repository is almost dead.

In terms of large partnerships, Brendan Blumer, CEO of Block.one, published a handful of tweets mentioning corporations, and the company’s senior advisor, Rob Jesudason, spoke at Asian Financial Forum 2019 hosted by PwC. And though EOS is a perfect fit for enterprises from a technological standpoint, its issues with BPs collusion is likely to get in the way of potential partnerships.

Instead of fixing EOS’s overarching issues, Block.one singles out certain in-house projects like Voice and focuses on promoting them. The company takes more risks by pushing several selected teams instead of creating an attractive environment for all the developers in the first place. Instead of making its previous projects successful, Block.one is following the money by launching more products that are likely to fail.

A Decentralized Operating System

Dan Larimer, Chief Technology Officer of Block.one, has a persuasive analogy for the EOS network: it’s a decentralized operating system.

In many ways, Larimer’s creation is, for all intents and purposes, better than Ethereum.

The network is scalable, pushing 4,000 maximum transactions per second. The blockchain is familiar for developers and accessible for dApp users. The developers who decide to build on the platform, despite the expensive barrier to entry, also prefer EOS to Ethereum and other Layer 1 solutions for many legitimate reasons.

However, the network failed to retain its initial community. Developers have peeled away to build on EOS forks, and users have followed. Ethereum, on the other hand, boasts one of the richest developer communities in the crypto space.

It will be challenging to return to relevancy, but one way that Larimer’s network could reemerge would be to join the bustling DeFi movement. EOS could find new life acting as a Layer 2 chain for a clogged Ethereum network.

With the help of projects like the DAPP network and LiquidX, EOS and its forks could then consolidate around Ethereum’s user base and piggyback on its activity. Instead of clutching to its title as an “Ethereum Killer,” EOS is perfectly positioned to be an “Ethereum Enabler.”

If Block.one can focus on its community, there’s no reason that they couldn’t push the decentralized finance movement far beyond its current marginal role in crypto.