EOS’ Biggest Problem Is Governance, Not The ICO

Short-term gain at the expense of long-term development.

The ICO question may have been settled last night, but the SEC could be the least of EOS‘ problems. Significant changes to the EOS governance model in recent months are casting doubt on the long-term sustainability of the platform, and raising questions about the decentralized nature of the network.

Rohan Abraham is the co-founder of EOS Authority, an official EOS block explorer and wallet provider, which was one of the original block producers for the EOS network. Along with twenty other BP’s, EOS Authority was responsible for securing the network in return for a share of the block reward.

“The original block producers, for the most part, were very technically minded,” Abraham explained to Crypto Briefing. Companies like EOS Authority were drawn in by the vision of an alternative smart contract platform and put a lot of work into it, with few guarantees of success.

“We just really liked the idea,” he said. When the platform finally launched in the summer of 2018, the original BPs fixed bugs and built out the ecosystem in return for a share of the block reward. EOS Authority used its block reward to create a whole suite of data tools, which it made freely available to the community.

But the status quo has changed since then. “Many of the original block producers didn’t have many tokens,” explained Abraham, and were gradually replaced by exchanges, like Binance, Huobi and Bitfinex, who used their large token pools to get themselves into the top-twenty one.

Things really came to head in April of this year, when the interim constitution was replaced by a new EOS User Agreement (EUA).

Passed by a vote of 15 of the 21 BPs, the simplified EUA outlined the responsibilities of the user and the BP. The most significant change was to omit a clause which explicitly forbade vote-buying. Aspiring block producers could now buy votes from the community, as well as from each other, in order to secure and hold onto their BP status.

Almost overnight, new entities, mostly based in China, came onto the scene offering a share of the block reward in exchange for the community’s votes. “If you’re a genesis token holder, you can either vote for one of the original block producers or you can actually vote for somebody who will pay you back,” says Abraham.

Sure enough, the original block producers began dropping off the schedule of BP candidates, either dropping onto standby or shutting down their services. Only a handful now remain, and even EOS New York, which first proposed the EUA, fell from fourth to its current rank at 33rd.

In early September, EOS Tribe – also an original BP – announced its departure from EOS altogether. In an official blog post, they complained that a “corruption” of the governance model means that BPs are now chosen in vote-buying deals rather than on merit, leading to a “mediocre performance” that culminated in failing transactions.

EOS Authority, which was once the second-largest BP by staked votes, is still holding on. It is currently in standby mode, meaning it is ready to secure the network should any of the active BPs shutdown. But whereas they had previously received 800 EOS per day, Abraham says that their income had now been slashed to just 200 EOS.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty for us,” he said. Besides hoping for an increasing token price to offset the loss in income, Abraham knows that this is not sustainable for the long-term. They have begun to feel the squeeze. “There were code reviews we used to do,” Abraham says, “but can’t now because we don’t have the budget.”

Lack of development funding

The change in allocations has a much broader impact on the EOS community. Whereas original BPs used funds to create tools and build the ecosystem, there’s a tendency among the newer generation to either keep the rewards for themselves or share them among their voters.

“All the funds that used to go to the founding BPs, who then made lots of API tools, are now been diverted into the hands of token holders,” Abraham said. In the short-term, that has already led to a reduction in ecosystem development and impacted many community-funded projects.

In May, BPs decided to burn more than 34M EOS held in the savings account because they could not agree on a mechanism to distribute it to dApps. A proposal to use the accumulated capital to create a Dev Fund didn’t even pass the initial voting stage.

The savings account, which is still live, holds more than $52M worth of EOS at the time of writing.

“The model is fundamentally problematic,” explains Jake Yocom-Piatt, lead organizer at the decentralized governance platform, Decred (DCR). Yocom-Piatt predicts a process of rapid centralization that will erode any communal consensus system, and replace it with “a thinly-veiled central-planning committee.”

Abraham is still not certain what the long-term ramifications could be, but he worries the community will soon have to start paying for features that were previously free.

One example is the plummeting number of History APIs, which allow users to search and track historical transactions. EOS Asia, which formerly ran one of the most popular History APIs in the APAC region, announced in November that it would discontinue support due to “cost concerns.”

While there used to be more than thirty companies offering History APIs, currently there are only one or two entities that are still able to offer them.

Can EOS fix its governance model?

Many fear that the EOS governance model is slowly being dismantled. Some of the biggest concerns come from the fact that the new BPs tend to be based in China. In August, the former EOS backer Brock Pierce complained that the network had turned into a “bit of a Chinese oligarchy.”

The delegated Proof-of-Stake model means that EOS can still achieve a high transaction rate with little community disruption. “But if all these are situated in one nation-state, that nation-state controls that network,” says Yocom-Piatt. EOS users could be surrendering the remnants of their sovereignty for better throughput.

Abraham is still confident that EOS will be able to adapt to the new reality, and the new BPs continue to vote on new proposals. Just last week, they passed EOSIO 1.8, which includes new features for the much-awaited ‘Voice‘ social media platform, as well as measures to protect users and dApps from spoofing attempts. A new smart contract feature is scheduled to go live later this month.

“There is no oligarchy,” said Abraham. EOS is still capable of effective governance, he insisted, and the BP list is changing on a daily basis. “Today there have been two changes to the schedule.”

But Yocom-Piatt believes that many of the platform’s shortcomings are already baked-in. The EOS network has “incredibly low voter-turnout,” he says, with some proposals only garnering around the 1-2% support. On Decred, even “crappy proposals” still get somewhere around 20-30% of votes.

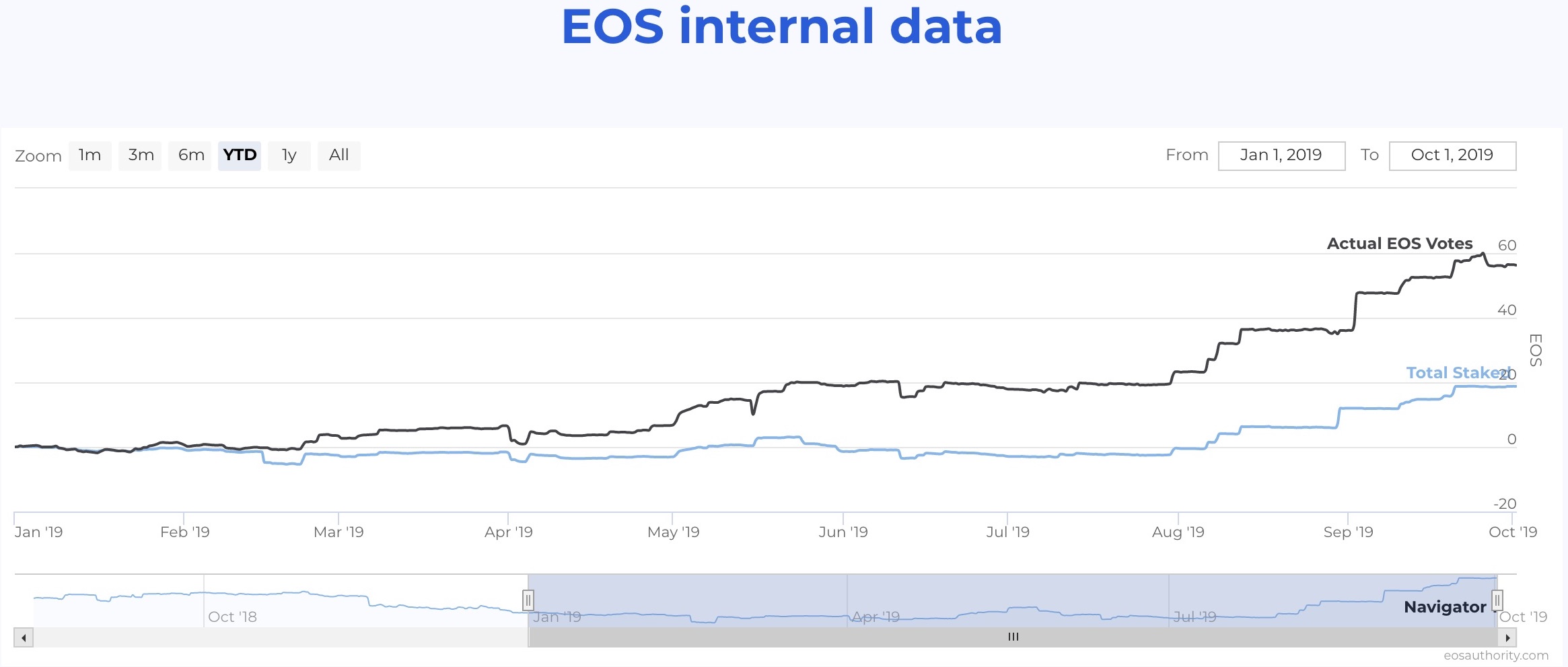

Votes may have increased since the beginning of the year, but the total staked hasn’t kept up. According to Abraham, that means that many users have not bothered to vote, and those that do vote tend to be exchanges.

“If anyone really cared about EOS, they’d be voting, ” Yocom-Piatt says. “When I see voter turnout that’s as low as it is on EOS, it means the investors do not care about sovereignty. They are there only for the money.”

EOS was riding high when it completed its ICO at the end of May 2018. Since then the project has been beset by technical issues and concerns about fiduciary responsibilities.

While Block.one will be grateful for yesterday’s decision, there are many other problems facing the EOS network. The token sale was the most famous of them, but compared to the problems facing its governance model, that might end up being just the tip of the iceberg.